The trip in was uneventful … until it wasn’t.

Two hours flat. Only one circling of the block to situate the car for parking at the hotel. And then we were on our way to TIFF Lightbox when our Uber drove through a stop sign and got pulled over.

What’s even the protocol then? We could have gotten out and walked, but would that have made matters worse? “Hello, officer. This does not concern us.”

So, we waited the twenty or so minutes—TIFF slightly delayed.

Then comes the email about bag size to worry about whether my laptop will be allowed into public screenings (it will … so far) alongside the confirmation that all public shows are assigned seating. Even traditional multiplexes like Scotiabank and Lightbox. There’s always a new wrinkle.

As for the day on the ground: it was a success. RIFF RAFF was a mess not without its moments (full review on 9/10). DANIELA FOREVER was a success not without its issues (review at The Film Stage soon). THE SWEDISH TORPEDO was a solid biopic that sadly too many press/industry people missed because of the big gala premieres (full review on 9/13). We were an audience of only about ten.

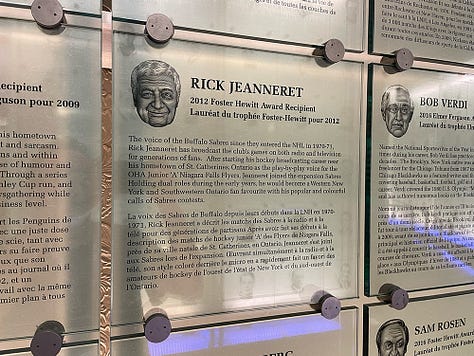

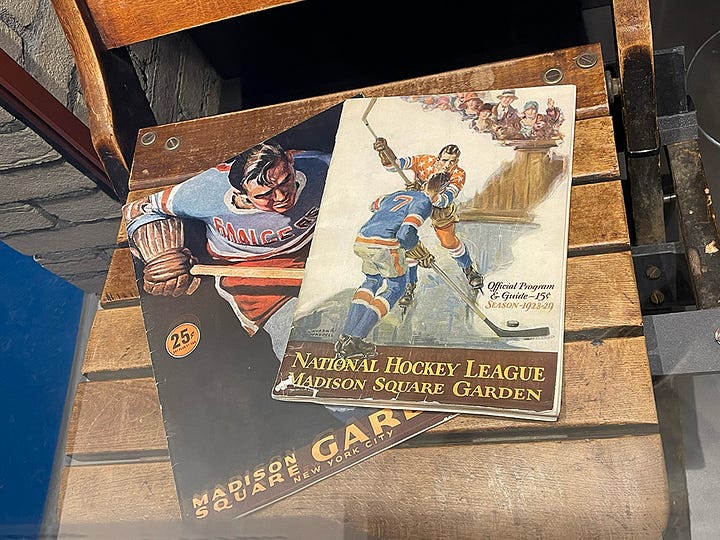

And to round out the day (courtesy of the good folks at Destination Toronto), I even got to visit the Hockey Hall of Fame for the first time in about twenty-five years. I hunted down as many Sabres names as I could via plaques (Ted Darling, Gilbert Perrault, Dominik Hasek) and trophies (Michael Peca on the Selke, Buffalo still surprisingly on the President’s Trophy), enjoying the museum for all its paraphernalia (curios, Original Six seats), displays (marginalized communities, teams, international jerseys), and interactive events. Had to find my guy Paul Kariya too.

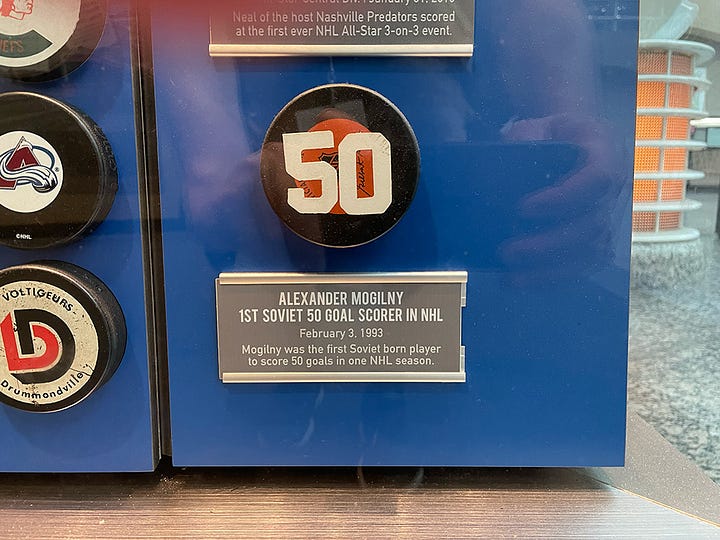

Then, on my way back to King Street I saw the wall of pucks—one of which was Alexander Mogilny’s 50th from the year he scored 76 to become the first Soviet-born player to hit fifty in a single season. They do remember who he is! Now they just need to finally enshrine him.

REVIEWS:

CAN I GET A WITNESS?

(World Premiere - September 6th - Canada - English)

The premise of Ann Marie Fleming’s CAN I GET A WITNESS? holds a ton of intrigue. Set in the not-so-distant future, humanity has figured out a way to solve Earth’s sustainability issues by rewinding the technological clock and placing a cap on life at fifty years. As such, those who work to keep communities going through equitable labor are the young—including those serving as witnesses to their elders’ “end of life” or EOL. Ellie (Sandra Oh) was one such witness in her youth and now her daughter Kiah (Keira Jang) is following in her footsteps. It’s neither glamorous work nor easy emotionally or physically, but it is necessary.

What I liked about the first half is that Fleming feels no need to explain anything beyond this premise. The dialogue given to Ellie as Kiah readies for her first day allude to the next two days being as much a beginning as it is an end and the events that transpire as Daniel (Joel Oulette) teaches his new partner the ropes provide all the implicit knowledge we need to understand their present is a product of our own. Every human being utilizes the smallest carbon footprint possible via a government quota of “credits” that ensure nobody impacts nature more than anything else. It’s a true egalitarian existence: living creature to living creature.

That level of implicit exposition unfortunately takes a hard turn towards the explicit once Daniel and Kiah end the first day with a group therapy session meant to help these teens cope with the heavy burden placed upon their shoulders. They are ostensibly grief counselors for the dying and undertakers for the dead who tell themselves they aren’t actually doing anything but standing witness despite their presence being what starts the process of benevolent suicide. Whereas you would expect this session with experienced witnesses to get to the heart of the philosophical nature of the job, however, it ends up being a sermon for us instead.

I don’t exactly begrudge the film for deciding to beat us over the head with what anyone with common sense knows just by looking out their window. That’s the message this sci-fi fable seeks to provide—an education about where we’re headed as a planet and the sacrifices that must be made to reverse course. My issue arrives from the narrative choice of making it so Kiah and all the other young teens alive in this new world also need that education. The back half of CAN I GET A WITNESS? is therefore an overt bullet point session explaining what someone who grew up in that world should already know solely for the audience’s benefit.

I’d argue this is the type of art that won’t be viewed by those who would benefit from its lesson, so rendering it a “preaching to the choir” piece that asks us to believe those living through it aren’t said choir makes matters even worse. Because it’s one thing to talk to us like we can’t understand the very obvious truths laid out by Kiah and Daniel’s job. It’s another to force us to suspend disbelief far enough that they are ignorant too. Maybe Fleming is attempting to bake in the lesson that it’s easy for us to turn a blind eye to what’s right in front of our faces, but the way she does so on-screen means Ellie (and other parents like her) learned nothing.

Because this is a woman who knows what life was like when you could own a car and fly across the globe in an airplane. She’s a woman who has witnessed countless people dying at fifty at a time when the new constitution had just been ratified and thus probably found a lot more push back than the “greater good” sentiments of today. And she’s a woman who raised a child under that rule with full knowledge of the path her very birth has set forth. We’re to believe Ellie didn’t prepare Kiah by teaching her what was and why it can never be again until right now? When we know what’s coming? At the literal eleventh hour? Sorry, I checked out.

And it’s not just because of the script. It’s also because I have no clue what the actual lesson being taught is as a result. Sometimes the film makes us consider that their world is a utopia because of everything they can still have. But most times it feels very dystopian in its reveal of what they can’t have. Ever. The end credits may have a blurb about going to the website to learn about ways you can help curb global warming and other issues plaguing our ability to stay alive, but my biggest takeaway from what occurs to these characters is that it’s better to have the freedom of destruction than the promise of peace.

I don’t think that’s what Fleming or anyone else involved were striving for, but that’s where I’m at. Rather than see the tough choices as a means to slow down and build a world where extinction is postponed, I see a nightmare that makes me wonder if we shouldn’t just speed things up. Because the lack of awareness on behalf of Kiah and Daniel makes me believe there’s no middle ground. Survival is about going cold turkey and embracing Marvel’s Thanos snap. So, rather than feel hope, I only have despair. Because I’d like to think the world is worth saving so our children’s children can live. Not to merely go through the motions and die.

- 5/10

THE MOTHER AND THE BEAR

(World Premiere - September 6th - Canada/Chile - English/Korean)

When Sumi (Leere Park) slips and falls in Winnipeg, leading doctors to put her in a medically induced coma so she can recover, the first thing her Korean mother (Kim Ho-jung’s Sara) thinks is that it never would have happened if she had a husband. A majority of her unanswered voicemails trade in the same topic—probably why they remain unanswered. Regardless, Sara cannot simply keep wishing her daughter will come home. Not when she’s healthy and definitely not now. So, she finally makes the journey to Canada herself to offer whatever assistance she can. Cleaning the house. Stocking the fridge with fresh kimchi. Setting up an online dating profile to find her a man.

Writer/director Johnny Ma knows this type of thinking isn’t simply a product of maternal parentage, though. The way the characters in his film THE MOTHER AND THE BEAR act proves it’s a Korean trait that afflicts both genders equally. Sara isn’t therefore the only parent on-screen who’s disappointed in their child. Sam (Lee Won-jae) is too. Not because Min (Jonathan Kim) is single, but because he’s dating a white woman (Samantha Kendrick’s Jennie). In a perfect world, Sara and Sam’s chance encounter would mean wedding bells for their kids. Well, their perfect world, at least. Because overbearing, traditional parents refuse to see that what they label “unorthodox” is actually what makes their children happiest.

That’s the lesson here. Unfortunately for them, though, the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree. To think your son or daughter is too stubborn to listen to (archaic) reason means you’re just as stubborn when it comes to understanding why. Sara and Sam are blind to it. They’re so wrapped up in their own desires that they cannot see how Sumi and Min will pull away in the belief that their chosen paths will never be accepted. And since she’s in a coma and he can’t put Jennie in the same room as his father without him storming off, Sara and Sam have nobody to open their eyes to that truth but each other. If they can stop making things worse first.

It’s really an ingenious way to tell this particular story because we’re so used to the fighting that comes with the generational divide. By mostly taking the children out of the equation narratively, we get to watch Sara’s journey towards clarity unencumbered by the usual clichéd conflicts. And since she doesn’t have Sumi to explain things (or reject them outright), she must jump into the fire without protection. That means getting her borrowed car towed for parking in front of a hydrant. Assaulting Sumi's friend Amaya (Amara Pedroso) when she enters the apartment to feed the cat. And even risking the receipt of a dick pic while pretending to be her daughter online after unintentionally eating an edible.

Add the fact that her attempts to find love for Sumi ultimately put her on the path to going on her own dates with Sam and the whole endeavor proves as heartwarming as it is funny. It helps that Sara is such a purely innocent character despite her actions being anything but. She’s doing it with good intentions and she’s not averse to learning the error of her ways once things spiral out of control enough to potentially ruin lives in the process. Because, at the end of the day, it’s Sumi and Min who can teach their parents something about living for today rather than yesterday. Maybe it takes screwing everything up to realize family—no matter what form—is all that really matters.

I have to give Ma a lot of credit too for rendering everything so authentic despite its familiar tropes. At its core, THE MOTHER AND THE BEAR is a fish-out-of-water tale with Sara coming to a foreign land to see that everything she prejudicially dismissed as being corruptible might prove profound. So, we laugh at the easy juxtapositions of her warm-blooded Korean dealing with the shock of cold, but also her tenacity to overcome and begin stepping into her daughter’s shoes to experience it with open eyes. And while most films of this mother/daughter variety inevitably have a vibrator joke, this one is refreshing because it allows the gag to be Sara’s ignorance of its use. Not its discovery.

It’s that level of respect for the audience that shines throughout. Whenever the chance for an easy bit of drama arrives, Ma deftly keeps matters subdued so that the payoff can come with intent rather than bluster. Not that he won’t add some flourishes like a full-blown karaoke filter transposed above one of the many revelations Sara discovers. Just because he’s not catering to the lowest common denominator for laughs doesn’t mean the sweetness with which he colors everything isn’t still undeniably fun. When you have a central performance like the one Kim Ho-jung delivers, it’s hard not to get caught up in the pratfalls and pathos alike. In the end, it’s Sara who needs to wake up and discover there’s more to life than habit.

- 8/10

PAYING FOR IT

(World Premiere - September 6th - Canada - English)

I’m going to take things one step further than Suzo (Noah Lamanna) and say Chester Brown (Dan Beirne) is so agreeable that he’d give me a kidney without ever meeting him. We’re not just talking about little things he did while dating her friend Sonny Lee (Emily Lê). This guy barely pauses for a breath when Sonny tells him she’s falling in love with someone else and wants to know if she can pursue it. Chester not only agrees while reconfirming his love for her, but his words are genuine. And that’s not even the most surprising part of this ordeal. That honor goes to discovering the result is the best thing that could ever have happened to him.

It’s all documented in Brown’s 2011 graphic novel and now in Sook-Yin Lee’s cinematic adaptation (co-adapted with Joanne Sarazen) PAYING FOR IT. And who better to bring it into this medium than the woman Sonny was based upon? The two have remained best friends for every year since even though that initial question in bed ultimately led them to dissolving their romantic relationship. So, don’t therefore expect any bitterness to permeate these frames. This is the tale of two very self-aware adults who realized the love they shared with one another wasn’t predicated on sex or obligation. They honestly just wanted to see each other happy no matter what it took for that to happen.

While Sonny is crucial to the whole, however, this isn’t quite the two-hander you might expect. She’s a big piece in Chester’s life during this period, but we generally see her through his lens despite Lee providing her surrogate character a few scenes without him. Sonny is a catalyst and confidant. Chester is the focal point embarking on a journey towards sexual and intellectual enlightenment. Because while she begins to date a revolving door of men with the aspiration of being a couple, he starts to pay a rolodex of women with the sole goal of sex. What we discover in the aftermath is that it’s much harder to fulfill one’s emotional needs than it is to satisfy their physical desire.

Despite playing it for laughs in the beginning, the fact that Chester’s physical desires are about as vanilla as possible (a couple thrusts to completion and a wide grin of authentic thanks) becomes a key piece to this very sex positive puzzle. He’s not looking for festish work or an excuse to laud his own prowess. He has simple wants and the budgeted funds to achieve them with a variety of compassionate and professional women looking to sustain a livelihood. Chester discovers that he doesn’t care for the inherently compulsory side of relationships. It’s not that he doesn’t want to be there for people he cares about. He just doesn’t want to water it down with the thought that it wasn’t a choice.

Is that an extremely cynical way to look at romance? Yes. Especially considering Sonny is correct to admit how Chester is probably the most romantic person she has ever met. But it isn’t fake either. That’s a credit to the character that Brown, Lee, and Sarazen all had a hand in creating on the page (and in life where the former is concerned) as well as the performance Beirne provides to bring him to life here. Nothing about his actions or line delivery on-screen feels forced or caricatured. Chester is an even-keeled guy who knows his limitations and sees them as a strength rather than a liability. He’s quite frankly an easy guy to love.

We therefore know why Sonny lets him live in her basement while dating other men. And why Chester’s many escorts wish all their johns were more like him. When Yulissa (Andrea Werhun) reveals post-sex that she knows who he is and is a fan of his comics, she’s worried it might turn things sour. Because for a lot of men it would. Our society’s ingrained misogyny purports that “real men” shouldn’t need to pay for sex and “worthy women” would never sell their bodies. But Chester doesn’t ascribe to any of that rhetoric. He values these ladies and the service they provide. It’s precisely because of them that he’s grown more confident in his own skin.

Let's face it: optics are everything. Suzo’s joke about Chester being easy going isn’t necessarily a compliment because the things he lets people get away with make him appear like a pushover (even to his trio of comic writer chums) in the context of a relationship predicated on certain culturally decided truths. Take those out of the equation, however, and he becomes a generous man to aspire towards. He goes from cuckolded loser to cocksure hero overnight precisely because he refuses to shy away from the reality that he gets all the love he needs from those he wants to hang out with when he wants to hang out. Sex is separate. They don’t have to mix.

As such, PAYING FOR IT doesn’t shy away from nudity or sex acts themselves. It’s both a sex positive film in terms of subject matter and content. So, if you aren’t as comfortable with the human form as Chester is, don’t be surprised if you find yourself feeling embarrassed while watching. But, like he says when he shares with Yulissa his idea to write a book about these experiences: watching might be exactly what’s needed to stop feeling embarrassed. Brown’s book and Lee’s film are meant to challenge the antiquated and oppressive norms with which our Puritanical indoctrination has branded us. It’s okay to break free. There’s no shame in being happy.

- 7/10

SHARP CORNER

(World Premiere - September 6th - Canada/Ireland - English)

Josh (Ben Foster) and Rachel (Cobie Smulders) haven’t even been inside their new dream house for a day before tragedy strikes. A drunk teen is unable to control his car around the curve in front of their property, leading him to drive headlong into a tree. One of the tires flies off its axle, smashing into their picture window to wake up young Max (William Kosovic) in his bed. It’s a harrowing experience—one that justifiably shakes the trio up. And while there was nothing they could do to prevent it or help out in the aftermath besides calling 911, Josh can’t stop himself from wondering if there should have been. If he was better prepared, might the driver have survived?

Based on Russell Wangersky’s short story, Jason Buxton’s SHARP CORNER presents a choice. Josh can either accept the fact that it’s not his responsibility to put himself and his family in harm’s way or he can tell himself that the risk is worth it if his presence is able to save someone’s life. Because tragedy will and does happen again. And the circumstances become worse each time. Rachel wants to leave. As a therapist, she knows the toll these crashes are taking on both Max and Josh. The only chance they have of putting it behind them is to literally do just that. Yet Josh can’t shake his obsession to make a difference. He can’t stop these horrors from putting each victim’s death onto his own conscience.

It’s a fascinating bit of psychology because one can rationalize his decision. Josh looks at his situation and searches for a solution not merely for his own wellbeing, but also for the strangers being drawn into his orbit. And yet, despite the idea sounding selfless on paper, we can’t help but agree with Rachel’s objective viewpoint that it’s actually the opposite. She sees the way his eyes light up when talking about the crashes. She hears the cadence of his voice when he tells the stories as though he was a part of them rather than just a bystander. Is it therefore a yearning for attention? Is Josh’s ambition less about saving people and more about public validation? This is his opportunity to be a hero.

Add the fact that he’s been passed over for a promotion and Rachel’s desire to alter their collective perception of this being a dream home to it being a nightmare breaks something inside of him. Josh refuses to give this illusion he’s created in his head up because it feels like a failure if he does. Another failure to go with his career setback. Another point of disappointment to go along with his increased drinking and complaints about doing work on the house. He starts to believe that his compounding personal resentments and regrets can be washed away if he just does this one thing to make them irrelevant by comparison. Unfortunately, Josh isn’t able to acknowledge the cost being paid.

The result is a slow-moving character piece made even slower by Josh’s character. Foster plays him perfectly as a meek, non-confrontational guy going through something that demands passion in ways that make it seem he’s never had passion for his wife and son. There’s a lot of staring and contemplating. A lot of losing himself to the moment by ignoring or forgetting his family and job so that his plans with these crashes can be fulfilled. The performance is so soft-spoken and clinically obsessive that it can sometimes elicit laughter in the sheer absurdity of the juxtapositions created. He becomes so oblivious to his own self-destruction that I almost expected a hard turn into full-fledged comedy.

That doesn’t happen, though. Nor should it. I think the pacing issues and tonal metronome behind Josh’s movements merely allow for a lapse of investment in the stakes on-screen. Eventually Rachel and Max become pushed so far to the side that they stop being three-dimensional characters and start solely being motivation for Josh’s refocused attention. I quickly stopped caring about whether his family was going to stay together because the film did too. That’s ancillary to whether Josh will see this desire through and if he will allow himself to help coordinate the tragedies necessary for him to be heroic. Has he fallen that far?

I’d love to see things tightened up—maybe chop a good thirty minutes out since so much of the mood-setting sequences had me losing patience rather than increasing suspense—but I can’t deny the effectiveness of Foster and the emotional turmoil born from the pervasive sense of ineffectuality that’s taken hold of Josh’s self-identity. There are some really good moments throughout, especially those points where his character is able to finally see clarity in his actions for better and worse. So, as long as you can get onboard with this family drama pivoting into a very narrow study of one man’s quest for purpose, you should find the experience worthwhile. Just don’t expect it to be anything more.

- 6/10

TODAY’S SCHEDULE:

WE LIVE IN TIME, d. John Crowley

THE FIRE INSIDE, d. Rachel Morrison

DO I KNOW YOU FROM SOMEWHERE?, d. Arianna Martinez