TIFF 2024: Day Three

The beat goes on.

The thing about seeing so many public screenings is that you end up catching introductions from a whole bunch of directors.

You have Nacho Vigalondo waxing on about how long it’s been since his last TIFF (joking it doesn’t seem that long until you release The Beatles’ entire discography was completed in the same span of eight years).

There’s John Crowley doing damage control to break the news that Florence Pugh and Andrew Garfield weren’t coming despite just premiering less than twelve hours prior. Everyone around me was SUPER bummed.

Then Rachel Morrison brings cast (including Brian Tyree Henry and Ryan Destiny) and crew (including Barry Jenkins) to the stage to help immortalize the moment of bringing her first feature to an audience.

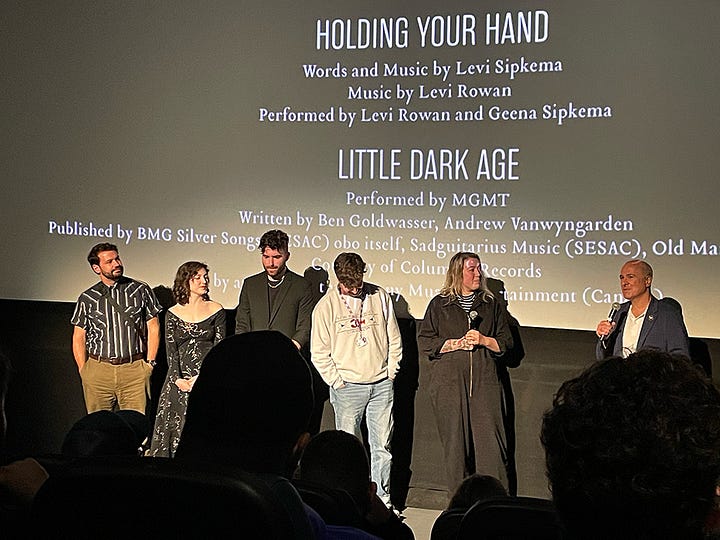

And, of course, high-energy, uber Canadian indie filmmakers like Arianna Martinez screening their latest to a small but very game theater who gasped when discovering the leads (Caroline Bell and Ian Ottis Goff) were also in the room.

It’s fun to experience that electric excitement from strangers who I so often hear just picked the film because the time worked and they new that one actor from something else. Like the couple behind me at WE LIVE IN TIME discussing their next potential target: “Sydney Sweeney is in it. Let’s find out who she is.” “You know her! She’s an up-and-comer.”

REVIEWS:

DANIELA FOREVER

(World Premiere - September 6th - Spain/Belgium - English)

“What makes the film so captivating is that Vigalondo doesn't shy away from the truth that there cannot ever be just one difference [between fantasy and reality]. Not when this parallel world is solely of Nicolás' making.”

– Full thoughts at The Film Stage.

DO I KNOW YOU FROM SOMEWHERE?

(World Premiere - September 6th - Canada - English)

It starts with a gift. Or the memory of one. Olive (Caroline Bell) knows she got Benny (Ian Ottis Goff) something—she’s just not sure where she put it, what it says, what it is, and, finally, that there was ever even something to remember. Is she losing it? Maybe. But then why does Benny begin to see and feel strange things too? His experience is additive. Hers is subtractive. And then suddenly he’s gone. To where? Not even he knows.

The disorientation is a feature, not a bug. Arianna Martinez’s DO I KNOW YOU FROM SOMEWHERE? (co-written by her husband Gordon Mihan) isn’t supposed to make sense. At least not yet. Because Olive and Benny are just as confused as we are. So much so that they begin to use one of the unexplainable anomalies (letter magnets on the fridge that aren’t theirs) to help find some answers. Doing so only creates more questions, though, since focusing on that which doesn’t belong inevitably anchors it to reality.

That’s when the flashback memories commence. First it’s the two of them recalling the day they met. Then it’s blurry figures standing in the corner of the frames behind them becoming sharper and clearer until we start getting flashbacks of them. It makes sense in the grander scope of the whole, but boy does pivoting off of Olive and Benny to follow Ada (Mallory Amirault) instead really snap you out of the trance Martinez had been weaving. I get wanting to add layers through other characters, but this isn’t their story to tell.

We recognize this as soon as Benny spells out things they mustn’t forget only to include himself but not Olive. Why? Because there’s no threat of forgetting her when everything we see is a product of her vision. Except that scene with Ada working. Olive wasn’t there. I guess she could have heard what happened, but the shift in perspective is one that doesn’t quite gel with the whole. Neither do the brief moments of Benny alone once the curtain is drawn to expose how he too isn’t there. Not really.

But he kind of is too? That’s the trick with movies dealing in multiple timelines (this is very much a multiverse script in the sense of a “what if” scenario rather than literal alternate dimensions, although one must imagine every possible outcome has its own dimension anyway so the distinction isn’t as important as you might assume). Vantage is key because it tells us who is aware and I’m not sure Benny should be regardless of whether allowing him the opportunity makes for a more coherent and impactful piece.

And when there are so many interesting questions being asked on-screen, allowing us to ask our own off of it only muddies the water. It’s an aesthetic choice, though. Martinez decides the pivot from Olive as sole orchestrator is worth the convolution. Maybe she’s right too. Maybe it actually does make sense when you watch it a few more times and break everything down. I’ll admit that it makes enough now to allow the ending an effective bit of poignancy. Maybe even enough to forget I had an issue in the first place.

So, I’ll definitely applaud the work—qualms or not. It’s clunky and stagy but has a massive amount of heart and pathos to compensate. It helps that Bell (in her first screen role) and Goff are so endearing. You look past the artifice to unearth a deep-seated love that shouldn’t be able to dissolve as rapidly as it is. Except, of course, that it must. Not because it didn’t happen or shouldn’t happen, but because the alternative demands its erasure. And that option is more. Not better. Not worse. Literally more. And that’s worth the sacrifice both for the one making the choice and the one who’ll never know it was even on the table.

- 6/10

THE FIRE INSIDE

(World Premiere - September 7th - USA - English)

“In the end, THE FIRE INSIDE is a sports biography with all the trappings you'd expect. It's a solid debut for Morrison and a star-making turn for Destiny with a message for girls and boys to know their worth and never settle.”

– Full thoughts at The Film Stage.

GÜLIZAR

(World Premiere - September 7th - Turkey/Kosovo - Turkish/Albanian)

It’s supposed to be a joyous time as Gülizar (Ecem Uzun) readies to marry Emre (Bekir Behrem) in a week. The plan is to take the bus with her mother from Turkey to Kosovo and meet him on the other side before getting the wedding details in order. Before they can cross the border, however, Gülizar’s mother is told she cannot pass because of an expiring passport. Not wanting to disrupt the very tight window in which they are working, the bride-to-be tells her mom to go home and get her paperwork in order. She will continue forward alone to ensure there are no delays and await the entire family’s arrival for the ceremony.

You cannot fault Gülizar for making this decision. In many respects, her mother still being on the bus probably wouldn’t have prevented what occurs. Because in a panic to retrieve the necklace her sister made her, Gülizar returns to the secluded bathroom she had just exited minutes prior without incident. Tragically, someone else was there this time seeking to take advantage of her haste. Regardless of whether Gülizar successfully fends him off to escape back to the bus, the incident remains a violent assault with lasting emotional and psychological scars. Add ingrained conservative traditions hinging upon “innocence” and admitting what happened feels like more of a liability than a necessary avenue towards healing.

Belkis Bayrak’s feature debut GÜLIZAR is very intentional in its expression of this reality. Not only does Gülizar not admit what happened, but she also tries to pretend like it never did in the hopes nobody will find out and ruin the wedding. Except there are bruises and obvious signs of PTSD. So, while she can hide it from Emre’s family (letting the crippling fear of being locked inside a changing room get their minds reeling about a cause), she cannot hide it from him. And when he tries taking matters into his own hands, his policeman uncle Bilal (Hakan Yufkacigil) reminds him their laws state that Gülizar wasn’t injured enough for serious action. Retribution only harms them.

Here in the US, the man who assaults Gülizar would be put in jail. There in Kosovo, he’d simply be outed in such a way that would mark her as being abused. What is there to therefore do but try and forget? And how can you forget when the crime can’t help but linger between these newlyweds whenever the prospect of romantic touch arises? Bilal does what he believes is his only course of correction: tell the couple everything has been taken care of and they’ll never have to worry about this random guy again. He hopes peace of mind sparks healing, but Gülizar runs into her assailant on the street anyway. And he isn’t just some random man.

The result is a tense affair that Bayrak orchestrates to perfection. Will someone get revenge? Will the assailant end up coming to the wedding? Will the rest of the family find out what happened? Will Gülizar and Emre ever be able to start their life together without it getting in the way? We’re dealing with systemic misogyny not only in the lax laws but also in the desire for blood. Because Emre’s anger is just as much a cause for their thus far unhappy union as Gülizar’s shame. What happens next should be her decision, not his. He should be listening to her needs and she should be provided more choices than just silence.

At only eighty-minutes, there’s little time to waste as far as letting events run their course against this celebratory backdrop. While the rest of the family smiles without a shred of suspicion, Gülizar and Emre rack their brains to figure out what’s next. Impulse gets the better of both—but more so him considering he chooses to bring her along as though to “prove himself” to her. Don’t think this fact is solely a product of machismo, though. Bayrak is careful to include another bit of back story that supplies Emre’s actions purpose beyond selfishness. The film is thus less about giving these characters closure than it is about exposing the audience to a grave cultural injustice.

The only way to move forward is for Gülizar to find a way to shut that door. Confronting Bayram (Ernest Malazogu) isn’t enough. Neither is allowing him to beg for forgiveness. And since there are no legal roads to satisfy this need, she must create one outside the law. Because something must give and suicide as a means of letting their families maintain the “dignity” of never discovering her pain isn’t an option. This struggle provides effective drama that gets to the heart of the character’s emotional core with Uzun beautifully portraying a sense of being lost alongside the fight to reclaim her life. It all culminates in an act that just might bring healing after all.

- 8/10

THE LEGEND OF THE VAGABOND QUEEN OF LAGOS

(World Premiere - September 7th - Nigeria - Nigerian Pidgin/Others)

“[The finale] showcases a movement where message surpasses character. Maybe it will feel less impactful to cinephiles as a result, but the Agbajowo Collective never lied about the PSA aspect being their main ambition.”

– Full thoughts via The Film Stage.

SEVEN DAYS

[Haft Rooz]

(World Premiere - September 7th - Germany - Farsi)

A cardiac event while in prison has forced the Iranian government to give Maryam (Vishka Asayesh) a seven-day medical leave. Imprisoned for six years as a women’s rights activist, the stipulations are made clear: she isn’t to engage in any political activity in-person or online and any act that defies this order will be hung around her brother Nima’s (Sina Parvaneh) neck for accepting her custody upon release. What nobody knows, including Maryam herself, is that her husband Behnam (Majid Bakhtiari) and Nima have hatched a plan to smuggle her over the border to safety. Whereas many dissidents might jump at the chance, Maryam must decide if the freedom to be with her children is enough to abandon her country.

Those are her words, of course. There’s no reason she couldn’t continue fighting abroad. Leaving Iran wouldn’t therefore be abandoning anything. Staying, however, would mean abandoning Dena (Tanaz Molaei) and Alborz (Sam Vafa) again. Does one render her less of an activist? The other less of a mother? These are the questions she must reconcile as she weighs the “selfishness” of leaving her kids with the selflessness of the reason why. Because it’s not a black or white issue. It feels like one to Alborz and Dena because they’re young and worried for her safety, but Maryam and Behnam know that some things are bigger than family. That refusing exile to continue working towards a brighter future in Tehran is about them.

Ali Samadi Ahadi’s SEVEN DAYS (written by Mohammad Rasoulof) reveals the stakes inherent to such an impossible decision. Because Maryam could refuse the plan. She could enjoy seven days at her mother’s home, calling and helping those in need, before going back to prison once they’re over. But six years apart is just as long for her as it is for her kids. To see them again might just be the salve necessary to keep pushing forward. Or it could be the final heartstring tug that makes her flee. So, she chooses to hedge her bets by risking everything twice. Once to survive the frozen mountains and border patrol to see her children. Once more to traverse them again before returning without anyone knowing.

Being able to see both parts of this struggle is important because it ensures we understand the danger faced. A lesser person would endure the paranoia and fear of riding in the trunk of a car and passing off cell phones without knowing if she’s being scammed and never want to experience it again. And that’s before trudging through the snow on horseback while avoiding bullets. Before seeing the frozen corpses of those who didn’t make it. Most would thank their lucky stars coming out the other side uninjured and do whatever it takes to stay that way. Because until she applies for and gains asylum, Maryam still isn’t safe from deportation. Asking her family to postpone so she can potentially go back is therefore a lot.

So too are the inevitable confrontations with her son and daughter. Alborz is ecstatic to hug her. Dena is justifiably enraged that her mother could put them through these past six years by refusing to leave Iran when given the choice between jail and banishment. But Maryam is correct when she’s overcome by emotion and forced to pull herself out of the corner in which guilt has trapped her. If she were a man, no one would dare label her a bad father. It’s because she’s a woman that she’s conversely labeled a “hero” and a “disgrace.” That’s what happens when you’re born into a nation that strips away your autonomy with an education system whose teachers tell young girls to just drop out and get married.

What makes the dynamic so powerful, though, is that Dena has thankfully not had to suffer the same fate due to growing up in Germany. As such, she can yell at her mother and tell her she never should have had them if she was always going to put her ideals first anyway because she’s been lucky enough to not have to make that choice herself. The very reasons why Maryam stayed are the reasons why Dena can exclaim those things with such fiery certainty. Unfortunately, just because she isn’t completely wrong to say them doesn’t mean she is right to disregard the context behind her mother’s motivations. It’s why we truly don’t know what Maryam will decide until the moment arrives.

It’s a beautifully performed role from Asayesh that’s devoid of easy answers. We watch Maryam run for her life and hope she escapes. Then her coyote (Zanyar Mohammadi) tells her “Iran is proud of you” and we understand how important she is to a cause desperate for her return. Then we see her smiling with her family and want to scream at the screen to keep running with them to Europe that instant. And if we’re yo-yo-ing that bad, it’s a miracle Maryam doesn’t have a heart attack on-screen from the stress of knowing her choice will dictate the rest of their lives. What everyone who begs her to finally live for herself doesn't realize, though, is that that’s exactly what she’s been doing these past six years.

- 8/10

SHEPHERDS

[Berger]

(World Premiere - September 7th - Canada/France - French)

You can’t help feeling jealous when Mathyas Lefebure (Félix-Antoine Duval) follows a very pregnant pause on the voicemail serving to cut all ties to his former life in Canada with these words to his former bosses: “You make me sick.” The relief in his smile—alongside the consolation that he’s still sorry for leaving nonetheless—is enough to fully invest in whatever road he decides to travel now that his credit is tapped in France. Yes, even when he chooses the insane idea to become a sheep herder in the Provence region without a shred of experience. Mathyas walks into a tavern of breeders with a pile of makeshift business cards asking them to give him a chance. Talk about bold.

Based on the 2006 book that Lefebure is writing on-screen via the sporadic narration that describes his state-of-mind after major events along the way, Sophie Deraspe’s SHEPHERDS proves an inspiring film about reinventing oneself outside of the societal conventions dictated by modern day capitalism. Mathyas was a slogan writer at an ad agency when he had his moment of epiphany to escape the duplicitously greedy world of corporate profiteering. It therefore makes sense he would decide to embark on a career whose margins have tanked as newly restrictive laws make solvency impossible. No one could dare tell him he was all talk and no action upon witnessing the “creature comforts” of this so-called dream.

He sticks with it, though. After an organized breeder regrets telling him he doesn’t have time to train a complete novice now that spring has arrived. After his first apprenticeship is with a crazy man whose wife neglected to explain why their previous shepherd suddenly quit. After surviving an apocalyptic lightning storm on the summit of a mountain (an unforgettably harrowing scene). Mathyas just keeps going. He doesn’t remain innocent considering what he’s had to endure and do himself, but his connection to nature only grows with eyes wide open. It helps that his metamorphosis into a nomad influences civil servant Élise (Solène Rigot) to join the adventure. The rewards overshadow the cost easier when you aren’t alone.

As Mathyas admits to Élise upon their reunion after a series of letters that romanticized his new occupation, shepherding is a violent job. While Deraspe does well not to show the acts themselves in gruesome detail (with the aftermath also proving tasteful thanks to a severed sheep leg being the most graphic things get), there’s no pretending that temper, stress, and grief aren’t firmly in control. Sometimes the violence is accidental where the consequences are concerned, but never in the lack of discipline that allows it to happen in the first place. Mathyas can look the other way for a lot knowing he’s still somewhat of an interloper. But, at a certain point, the continued assault on decency becomes unjustifiable.

It’s a truth both he and Élise must reconcile. And maybe they can since this isn’t something that’s been in their blood for generations. Whereas men like Ahmed (Michel Benizri) and Tellier (Bruno Raffaelli) know nothing but the back-breaking hours and anxiety that comes with one mistake costing you everything, Mathyas has perspective. If abuse isn’t working, try something calmer. Maybe you can love these animals and want to protect them instead of dismissing them as property to bend to your whims. This is the danger inherent to dying trades. Those born into it resent it and outsiders drawn to its romanticism are scared away. Neither side can be blamed considering the tightrope act takes more than it gives.

That’s why Mathyas is poised to rewrite the story of herding. He’s seen the hollow existence of city life and knows the soul-sucking nature of sitting at a desk for years with nothing of substance to show for it. So, when he looks at his scarred and calloused hands after a year of farmwork, it’s not a sign that he should quit. It’s a testament to making a difference. He’s no longer living for himself with hundreds of sheep now under his wing. And the life and death attitude he once experienced on the eve of made-up deadlines becomes quaint considering this job is truly about survival. The lives of these animals and the communities that rely upon them literally hang in the balance.

Duval carries the weight of that fact in his performance. We see it both when he can’t stop himself from breaking down in response to the horrors surrounding him and when he’s able to stand still and bask in the glory of the demanding yet rewarding life he’s begun to carve out of the French countryside. The supporting cast is great thanks to the aforementioned actors, Guilaine Londez, and David Ayala. And the cinematography captures the magisterial nature of this centuries-old art whether in claustrophobic pens or wide expanses of green grass. It’s brutal in its beauty, but also tangibly real in its seemingly foreign realm of existence. Mathyas will never take his comfort for granted again.

- 7/10

THEY WILL BE DUST

[Polvo serán]

(World Premiere - September 7th - Spain/Italy/Switzerland - Spanish/English)

The line that sticks with me from Carlos Marques-Marcet’s THEY WILL BE DUST (co-written with Coral Cruz and Clara Roquet) is when Flavio (Alfredo Castro) tells his youngest daughter Violeta (Mònica Almirall) that he’s “just” her parent. Sure, parenthood means something. The bond between a parent and a child should be an unbreakable one. But we understand his meaning. He’s supposed to die before her. We grow-up knowing we’ll inevitably need to say goodbye. So, doing it early shouldn’t be the end of the world. Especially not if “early” means “on his terms.” Violeta doesn’t need him anymore. She should enjoy her own life away from him like her siblings do. It’s not his job to help her accept his decision.

Claudia (Ángela Molina)—Flavio’s partner and Violeta’s mother—has been diagnosed with a terminal brain tumor and doesn’t have long to live. His decision is to therefore not only be by her side as she chooses to pursue assisted suicide in Switzerland, but to also leave this world with her. Flavio says it’s something he’s thought about for a long time. Well before her prognosis. We don’t quite learn the details, but from the way Violeta, Lea (Patrícia Bargalló), and Manuel (Alván Prado) talk, it seems like he left them at some point during their past before returning. One could say he’s experienced life without Claudia and knows he never wants to do it again. So, her death will be his and they’ll spend eternity together too.

The narrative is thus a familiar one. Flavio and Claudia must wrap their heads around what it is they are about to do and find a way to tell their children. What makes it unique is the way in which Marques-Marcet and company allow these two characters to hold steadfast in that decision no matter what anyone says in response. Yes, they will feel guilt when it comes to leaving their kids behind, but they must follow their hearts regardless because their wants are just as relevant and important as the ones of those they raised. They want Violeta and the others to accept it even if they cannot agree because they hope they’ve earned the respect that they are doing this without regret.

And since this is an artistic family (Claudia is an actor/dancer and Flavio is her director), the aesthetic can move past the usual somber tone of such stories by injecting a little theatrical fun by way of the tumor. Because beyond causing pain and disorientation, each jolt in Claudia’s head transforms the resulting scene into a musical number. Paramedics gliding through the apartment in chase, propping up what she throws down in their way. Choreographed dances on a bus and synchronized performances down a hallway in coffins. It’s as though her mind is grabbing hold of her identity, reminding her of who she is and the joy of life despite being helpless to prevent the curtain from coming down.

It’s the sort of levity we need to counteract the sorrow of the subject matter and anger that arises once everyone is made aware. Everything Claudia and Flavio do before telling the kids is colored by their secret. Her not wanting Violeta to put her career on hold, knowing it won’t be for as long as she assumes. Him concocting a wedding to ensure their older kids visit—even though most of the reason for not being able to just ask them over is a product of his role in the estrangement thanks to always giving their art precedence. We want there to be some big cathartic moment of forgiveness, but things don’t always work out that way. To Lea and Manuel, they are “just” parents.

Violeta’s place in this story is thus a crucial one. She’s close enough to Claudia and Flavio to not want them to go but also in the same boat as her siblings to realize it isn’t up to her. Having those three distinct positions really fleshes out the emotional beats so that THEY WILL BE DUST never risks falling into some melodramatic us-versus-them or right-versus-wrong soapbox. The script never questions anyone’s actions as being anything but genuine. The pain. The happiness. The longing. The desire. No one is looking at someone else to tell them it’s okay. They must each come to that clarity on their own knowing they love each other anyway. There’s no fault to be had, only understanding.

That goes for Claudia and Flavio most of all and both Molina and Castro perform them beautifully. The strength of their bond. The sadness in willingly leaving the others behind. What we see in their faces when confronted with the rage of those who’ve learned the truth is uncertainty. It’s fear. Just because they’ve decided to die together doesn’t mean they aren’t afraid. Afraid of what their kids might think. Afraid of the act itself. We never see them second-guess themselves, though. Only come to terms. The honesty in that distinction is impressive because it centers them as romantics afraid to die rather than self-centered souls seeking an escape. For them it’s not an end. It’s simply what’s necessary.

- 8/10

U ARE THE UNIVERSE

[Ти – Космос]

(World Premiere - September 7th - Ukraine/Belgium - Ukrainian/French)

Two years there. Two years back. Andriy (Volodymyr Kravchuk) has been piloting a long-haul spacecraft for a decade now—flying out to Jupiter’s moon Callisto to send Earth’s nuclear waste towards its surface before flying back to do it again. He’s never been much of a people person, so the isolation never bothered him. He sculpts plasticine to pass the time, listens to his records, and plays chess with the ship’s AI robot Maxim (Leonid Popadko). There’s no reason for him to take a break because he enjoys the quiet of space. But when a bright light blasts through his windows only for Maxim to explain Earth exploded, Andriy wants nothing more than to go back.

Well. Maybe not at first.

Pavlo Ostrikov’s U ARE THE UNIVERSE follows up this devastating news by showing Andriy getting drunk on medicine and dancing. He’s not celebrating the demise of his species. He’s probably just in shock. But he cannot help embracing the high of knowing he’s the last human alive. All that time away from home with all those people calling him crazy and now Andriy gets the last laugh. So, he throws out his routine. He makes a giant sandwich because rations are meant to keep you alive to be saved yet there’s no one left to do so. And he screams into the void, pretending to be a radio DJ playing his favorite tunes for a vacuum of stars.

Except someone is listening. It takes three hours to travel to him, but Catherine (Alexia Depicker) sends a message to tell Andriy he isn’t alone after all. And after getting to know each other through brief messages as though they are pen pals rather than the last remnants of an extinct life form, the opportunity to meet arrives via a risky “what if?” Since the debris from Earth’s destruction has all but debilitated Andriy’s ship, he must wield the sort of ingenuity for which a pragmatic computer such as Maxim wouldn’t approve. Some things go right. Others go very wrong. But what’s the point of living safely without anything to live for?

Therein lies the main theme at the back of Ostrikov’s film. Maxim’s mission is to keep Andriy alive, but for what purpose now that Earth is gone? All the code and rules in the world can’t erase the fact that his protocols are destined to fail regardless of whether he helps expedite the timeline or not. So, why not roll the dice? Wouldn’t a couple days or a few hours with someone else be better than months or years alone? Because Catherine has a much faster clock on her existence. Without fuel, Saturn’s gravity will soon tear her ship apart. Maybe it’s a longshot, but Andriy would rather try and fail than not know. To meet oblivion head-on together instead of going crazy begging for it all to end.

It’s a one-man show as a result. Yes, Maxim and Catherine are interacting with Andriy to keep things moving, but it’s all Kravchuk as far as emotional and dramatic weight go. His frustrations. His hopes. His regrets. The more he talks to the computer, the more we see how much he needs another human to remind him of life’s purpose. The more he talks to Catherine, the more we discover the reasons he’s been doing this job for as long as he has. Andriy is a mess. He goes one hundred miles per hour or not at all—grounds for Catherine to justifiably get freaked out and for Maxim to potentially manipulate him away from his goals.

The middle third can drag a bit as a result of this trio feeling each other out and measuring their words, but it’s not without reason once new revelations come out to turn the plot on its head. Nothing is too surprising since there are only so many options when you have so few characters and nowhere to escape to, but where Ostrikov takes us is both devastating and hopeful in equal measure. That’s no small feat either considering the only logical conclusion is death. Being able to reach that point with grace and beauty despite the growing tensions and uncertainty that risk a complete implosion of the tenuous relationship built proves a resounding success.

I loved the production design and the ability to make a one-room film feel more expansive than it is. The electronic “eyes” on Maxim’s robot screen augment Popadko’s vocal performance. The use of food and plasticine help give us an entry point into Andriy’s state of mind. And then there’s a brilliant piece of visual comedy—complete with Richard Strauss music cue from 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY—courtesy of a bright red chair to brighten Andriy’s day. Add the very bad “Dad jokes” and a believably cringe declaration of love and we end up witnessing a real microcosm of life through the eyes of an introvert who escaped Earth to avoid the sadness of living alone only to ultimately discover the dignity of dying together.

- 7/10

WE LIVE IN TIME

(World Premiere - September 6th - UK/France - English)

“Garfield and Pugh are also just plain adorable in their capacity to shed all pretense of celebrity and embody an everyman vibe ruled by desire. They're very funny in that way to alleviate the heavy weight that cancer holds on a movie like this too.”

– Full thoughts at The Film Stage.

TODAY’S SCHEDULE:

SKETCH, d. Seth Worley

ALL OF YOU, d. William Bridges

HERETIC, d. Scott Beck & Bryan Woods