It’s wild that the Golden Globes are still a thing. Wild because its corruption, secrecy, and lack of inclusion killed it once only for it to be revived by the conflict of interest that is Penske media—yes, publisher of pretty much every awards prognosticating website treating journalism as marketing while selling ads to the studios to whom they are now giving awards.

Perception is king, though. Decades of commercials equating Globe noms and wins with their Oscars counterparts has duped the general public into thinking the distinction means anything more than a potential bribe. Oh, THE TOURIST was nominated for Actor, Actress, and Picture (Comedy or Musical) in 2011? Must be a masterpiece!

At least it used to be fun with drunk comedians lambasting a room full of drunk marks. I did always enjoy Ricky Gervais, Tiny Fey, and Amy Poehler cutting jugulars. Maybe that’s still true. I haven’t watched in years and I don’t know who this year’s host (Nikki Glaser) is.

Ah well. Watch it on Sunday if you must.

While no awards were given, I did drop my corruption-less picks for the best twenty-five movie posters of 2024 (for releases in the US) over at The Film Stage. There were some real gems and I was actually able to hunt down an artist credit for each one (hopefully correctly). Check it out here as well as a list of most of the artists’ Instagrams here to see more of their work.

What I Watched:

CROSSING

(streaming on MUBI)

Istanbul: a place to disappear or a place of rebirth? It's really up to the eye of the beholder. Those being left see it as the former. Those doing the leaving as the latter. Especially in the case of Tekla, the twenty-eight-year-old niece Lia (Mzia Arabuli) has decided to find many years after she last saw her. Even that can be looked upon in one of two ways: a little too late or it's about damn time. Lia sees it as a bit of both considering her mission is half about fulfilling Tekla's mother's deathbed wish and half about atoning for her own sin of letting her leave. Because it's not lost on the audience that Lia does talk about her niece. The trans aspect doesn't seem to be an issue now. But it surely was then.

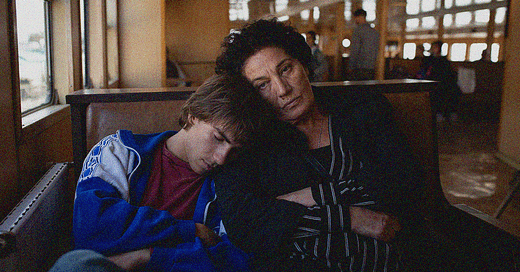

Levan Akin's Crossing follows Lia and the half-brother of her former student (Lucas Kankava's Achi) leaving Georgia to search for Tekla in Turkey. Achi says he used to smoke with her and that she had friends in Istanbul, so Lia agrees to let him be her translator in exchange for paying his way. Their relationship is guarded at first due to her inability to trust he isn't using her for his escape, but it's never not sweet in tone as far as the disappointed "mother" versus exuberant "child" dynamic goes. She wants to assert control and he wants to experience a new place (his "it looks the same" upon crossing the border is delivered with such innocent surprise as though he assumed every country has its own separate reality). It's not always smooth, but it's never without compassion.

Running parallel to their quest is Evrim's (Deniz Dumanli) journey for legitimacy in a place refusing to take her seriously. A trans woman herself, she volunteers at an NGO while awaiting her ID card to officially practice law off a newly minted degree. That pursuit comes with many of the issues that face the trans community everywhere: the constant assumption she's a sex worker, the need to pay bribes to every hospital department for them to sign off on legally changing her gender, always being disappointed by a boyfriend who won't be seen in public with her, etc. It's a necessary glimpse at her struggle that complements the experiences of the sex workers Lia meets first. They show her that Tekla's smarts and promise mean nothing without a support system to foster them. A support system Lia should have been.

The plot unfolds with straightforward drama as Lia and Achi learn to accept who the other is and what they have to offer in the absence of her niece and his mother. They create a cute makeshift familial bond with an always winking eye since neither is afraid to hustle others for free food or information. We're asked to presume that this stuck-up teacher and her screw-up companion are polar opposites before finding they're two peas in a pod. That they have something to offer and can appreciate what it is. Achi gets a taste of the loving discipline he lacked growing up without his parents while Lia discovers she has the maternal instincts to be what Tekla needs ... if she's lucky enough to find her.

Akin isn't here to make a fairy tale version of reality, though. This isn't some wide-eyed attempt to show the utopian ideal of the trans experience with an accepting family member. No, it's an attempt to humanize the trans community so families and friends who have rejected the trans people in their life might realize their bigotry is theirs to own. They can't blame their child for being trans. They can't blame society for their hate and fear. They can only blame themselves for voluntarily placing conditions on their love. It means something to hear the sex workers joke that they don't want their families to look for them and Evrim's trepidation about helping Lia just in case her motives aren't pure. The world has forced them to look after their own because it constantly shows it won't.

The resulting moments of implicit acceptance are thus more profound than anything that could be spoken from a soap box because we're watching simple, authentic interactions. To see Lia and Achi enter the trans community with open hearts and ears is meaningful. Watching them dance with Evrim at a wedding and to have that wedding's guests invite them in is meaningful. We've moved from Achi's brother telling Lia to not even try finding her niece because she's a "stain" on the family to Lia and Evrim hugging outside a hostel for no other reason besides shared humanity. Akin opens the film with text explaining how Georgian and Turkish are genderless languages, but it's only at the end that we're surrounded by characters who aren't judging each other for it.

And the finale? It's one of the year's most memorable scenes. I don't want to give too much away, but my initial smile of acceptance that this sweet and hopeful film would choose to go where it does eventually turned to tears as Akin pulls back to reveal the choice was a path towards introspective epiphany rather than convenient relief. It's the perfect bookend to contextualize everything that came before as more than a superficial adventure undertaken out of blind duty. It instead proves itself to be a deeply thought-provoking rebirth for Lia herself. Not in the sense that she's changed who she is, but that she's finally willing to accept her complicity in a grievous error that may never be able to be rectified. The hope is that someone watching might still have time to fix theirs.

- 9/10

FROM GROUND ZERO

(limited release; Palestine’s International Oscar submission)

Twenty-two short films about survival, oppression, dignity, fear, and hope make-up From Ground Zero's first-hand account of life in Gaza amidst Israel's current attempt to destroy all trace of Palestinian life. Created by Rashid Masharawi, a selection committee went through each pitched idea to curate the artists chosen before also working with them to ensure the integrity of the production and fulfillment of the mission. Most are non-fiction documentary/testimonials (the most effective of the bunch) with some live-action and animated pieces mixed in. No matter your opinion on the success of each, however, the whole is an undeniable document of an unspeakable tragedy. As a puppet declares during "Awakening": everything is gone and the world just watched.

My favorite of the bunch is probably "Taxi Wanissa" because of Etimad Washah's honesty about her struggle to make it during a time of impossible uncertainty. What starts as a fictional drama set amidst the destruction that follows a "taxi" driver ferrying citizens around on a donkey cart abruptly cuts to black before the filmmaker appears to explain why she couldn't finish. Her words epitomize the situation with devastating clarity because creating art in a time of war isn't just a physically daunting task, but also an emotionally draining one. When you're constantly forced to endure these horrors, the line between catharsis and masochism all but disappears. Because these films aren't being made with hindsight. They are depicting an ongoing nightmare in real-time.

And no one can escape that reality. Not the woman stretching one five-gallon container of water in "Recycling" to fulfill the all-in-one needs of hydration, dish washing, bathing, and sanitation. Not the young lovers in "Jad and Natalię" who can't know if putting off their engagement might ensure it never happens. Not an artist in "Out of Frame" who watched as the university meant to platform her career was bombed and then her entire portfolio erased once her home met the same fate. Not even the children in "Soft Skin" who must grapple with the heartbreaking purpose behind their mothers writing their names on each of their limbs. Not when "24 Hours" tells the fate of a man who survived three attacks in one day—two of which left him completely buried under rubble and in need of rescue.

It's tough for the fictionalizations to compete with such pain and suffering even though they come from the same place. Something about their polish and artifice takes us out of the moment the rest creates. I don't blame them—they're probably quite good when removed from the whole. It's the juxtaposition that does them no favors because nothing can compete with reality. The same can be said about the more hopeful vignettes like "No" and "All is Fine" to a lesser extent too. I love their message and their subject's strength to fight the good fight to keep victims laughing, but it's a hard sell amidst so much violence. It's easy to dismiss them as being naïve despite knowing that's not the case. Switching your brain from PTSD flashbacks in "Echo" and body bag sleeping bags in "Hell's Heaven" to joyous larks is tough.

There is necessity to it, though, because this project needs an injection of that resolve to truly become the well-rounded experiential work it is. Despite wanting to make sure the world witnesses the atrocities too many continue to ignore, you don't want to also add to the demoralizing futility of those living through it. The beauty of humanity is our ability to survive and bounce back, so you can't let Palestinians give up faith that this war will end with a return to their land. You can't let the children raised under a normalization of death and destruction lose hope when art projects, comedy routines, and concerts can coax them back from the edge of despondency in an instant. In many ways, their ability to keep smiling is the most powerful weapon of all.

- 7/10

THE GIRL WITH THE NEEDLE

[Pigen med nålen]

(limited theaters; streaming on MUBI soon; Demark’s International Oscar selection)

A young Danish seamstress (Vic Carmen Sonne's Karoline) can't afford her rent on paltry wages. She can't supplement that income with a widow's benefit either since her husband (Besir Zeciri's Peter) has yet to be declared dead despite having gone missing a full year ago. So, you can't blame her for falling under the spell of her wealthy employer (Joachim Fjelstrup's Jørgen) once he is "touched by her story." To have hope for a way out? Hope for new love? Hope for a family? From being a few kroner away from living on the street to wearing a fancy dress with the promise of marriage and status? It's a literal dream come true.

That's when director Magnus von Horn pulls the rug. Because right as things seem to be trending towards happily ever after, he and co-writer Line Langebek Knudsen point the camera outside the doors of Karoline's work at a solitary man standing in the distance. We know right away who he is—even before he begins to shout her name. Peter has returned. Injured, traumatized, and burdened by shame. Rather than lie, however, Karoline admits she's fallen for someone else. She admits her pregnancy. And she asks Jørgen to marry her. Best friend Frida (Tessa Hoder) is correct to call her brave because life is never that easy. Especially not in 1919 Copenhagen. Especially not for a woman.

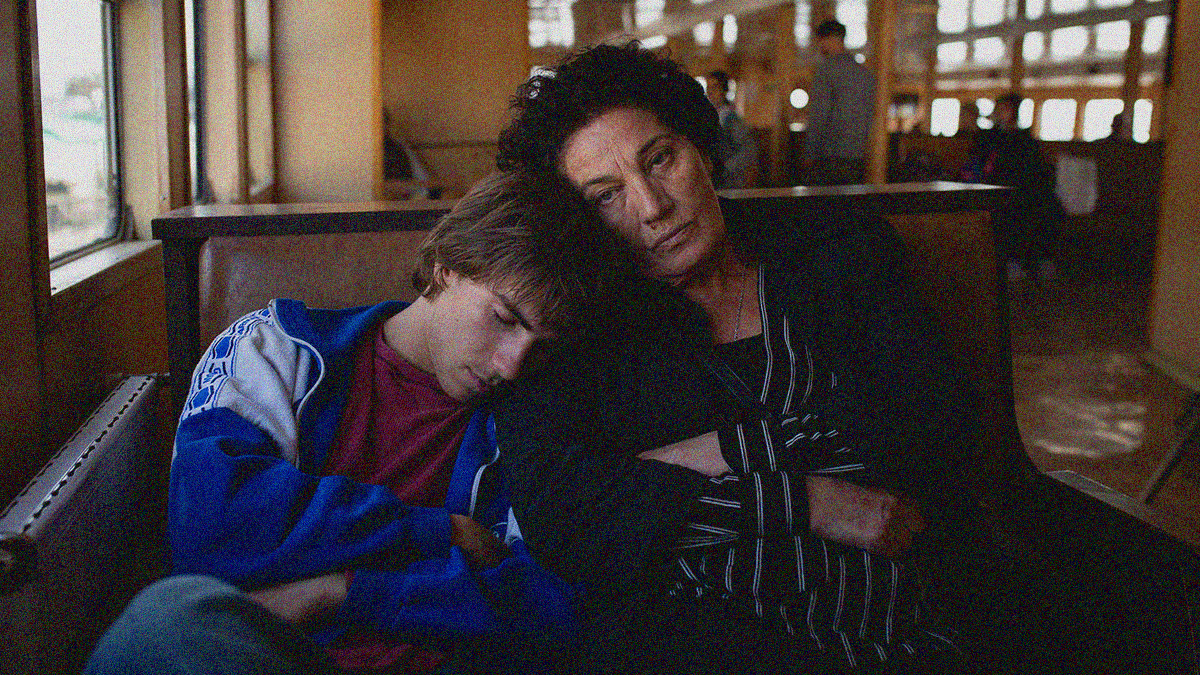

One blow follows the next as The Girl with the Needle inevitably makes good on its title with Karoline smuggling a giant metal spike into the bathhouse to give herself an abortion. That's where she meets Dagmar (Trine Dyrholm) and her daughter Erena (Ava Knox Martin) promising a happier ending for both mother and baby. If Karoline is willing to carry the child to term, Dagmar will find it a good home ... for a price. And, in a fit of desperation, maybe Karoline can help do the same for others in similar circumstances. Because it doesn't matter that buying and selling babies is illegal. It's worth the risk to give women with no other choice the chance to live without the burden placed upon them by men.

The script is pretty straightforward for the first two-thirds or so as a result. Contrast points abound whether the cruelty of a mother slapping her child in the face at the start opposite Dagmar's warmth towards Erena or Peter's compassionate "freak" opposite Jørgen's well-to-do coward. Karoline is forced to travel between worlds, watching those with everything squander their souls while those with love to share are left destitute. Yes, she often goes where comfort seems easiest devoid of loyalty—but it's not like anyone else has ever been loyal to her. Peter never replied to her letters that he was alive. Jørgen chose wealth over responsibility. Maybe Dagmar will be different. Maybe this partnership can be built on trust.

Well, prepare yourself for a wild, heartbreaking, and ultimately hopeful final third as von Horn discovers there's an infinite number of rugs beneath Karoline's feet that can still be yanked. Both Sonne and Dyrholm excel here as their characters attempt to salvage the life they longed for despite the truths that have made doing so unsalvageable. What packs an even bigger punch, though, is the way that their actions are actually serving as commentary on the world at-large—at the tail-end of World War I, but also today—when it comes to motherhood, bodily autonomy, and economic systems to care for the children that moral outrage foists upon the populace. What's happening is unspeakable, but it also proves to be a service society's collective ignorance demands.

- 8/10

LONGLEGS

(VOD/Digital HD)

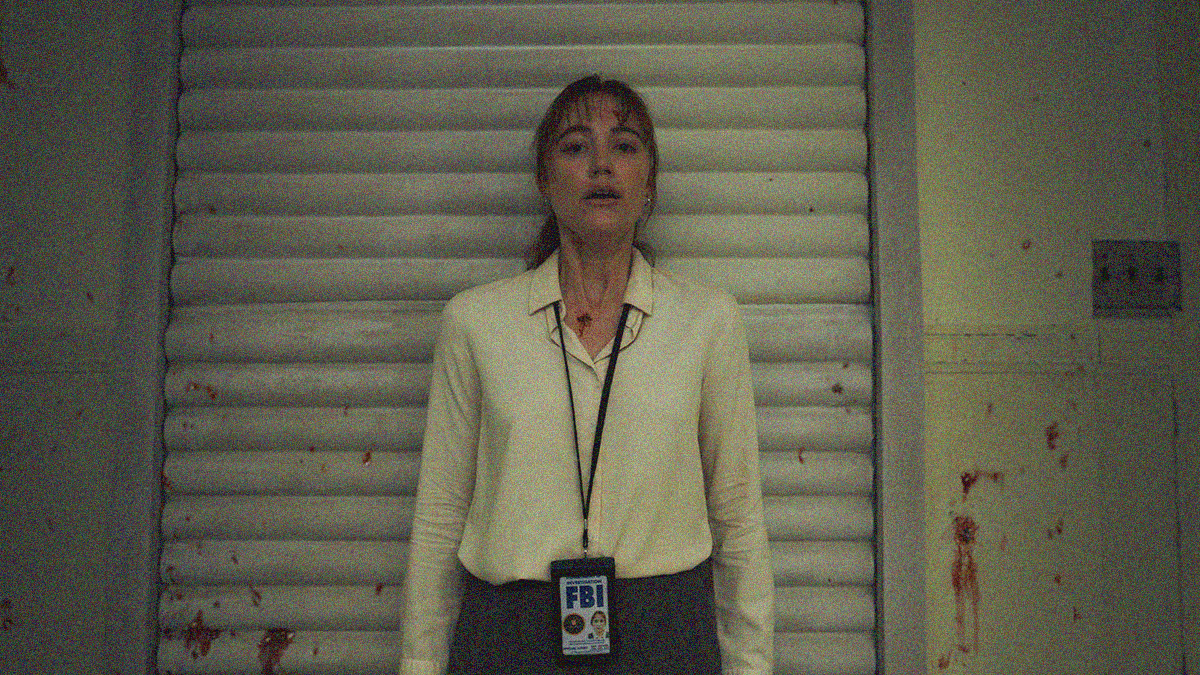

It felt like a tap on the shoulder. That's how Agent Lee Harker (Maika Monroe) described the gut instinct to know a murderer was inside the house across from the one her partner was canvassing. Agent Carter (Blair Underwood) jokes that she's clairvoyant. Lee simply brushes it off with her unwavering stoicism as a thing that just "happens sometimes." Whatever the cause or intention, the Bureau isn't about to let the possibility of an ace up their sleeve go to waste. So, despite her lack of experience, they assign her the most high-profile cold case they've got. And the moment she starts digging in is the moment he kills again.

Osgood Perkins labels the film the same way he does the man: Longlegs. Stemming from a creepy prologue wherein the pale serial killer (played by Nicolas Cage) accosts a young girl by crouching down right after saying he "left his long legs on," the cryptically absurd nature of the joke and the Longlegs look is a feature that intentionally toes the line between disturbing and farce. So does the robotic nature of Harker's introverted obsessive with zero interpersonal skills. Both teeter towards over-the-top on their respective ends of the spectrum with Cage singing his demands like a nursery rhyme and Monroe looking as though she's clenching her jaw to hold back an aneurysm.

The question for us to think about is how these two figures are connected since he seems to know her very well. Not in a cat and mouse chase kind of way, but a "welcome back" to my sphere kind of way. Because Longlegs has been getting away with it for years. He's so good that no one would ever have suspected his crime scenes were connected if he didn't leave cyphered notes with his name on them. Each one is a family and the forensic evidence all points to murder suicide inside the houses with weapons they own and no signs of anyone else being present. So, the decision to literally give Lee the key to everything seems less like a surrender than a smile. It's as if he's been waiting for her.

Longlegs proves an interesting beast as a result because it unfolds like a serial killer movie despite not really being a serial killer movie. The draw is Lee hunting for this monster and the wild discoveries made along the way, but nothing that happens is truly a result of police work. Everything is orchestrated to the smallest detail—so much so that even the good things feel wrong because we've been trained to believe they're means to a new nightmarish end. This fact adds a ton of suspense and intrigue in the moment, but a lot of it begins to fall apart the more you think in hindsight. Don't therefore think too much when the screen cuts to black. As more strings reveal themselves, the greater chance of you wondering if there was a point.

Not that there needs to be a point. I'm a glutton for taut storytelling and eccentric characters regardless of how they come together too. But it's tough to move from very good and entertaining to masterpiece without there being a bit more meat on the bones. Perkins sort of hedges his bets in a way that undercuts the police thrills with horror just as he undercuts the horror with those same police thrills. It can't be a great version of either if the other prevents it from moving beyond pure mood. Longlegs is scarier as a man than he is a monster and the case is more captivating as a crime than it is a ritual. I had a blast, but I do wonder how much better it could be if Perkins picked a lane. Alicia Witt and Kiernan Shipka's effective supporting turns might not feel so wasted.

I can't be too disappointed, though. Not when you get Cage going full-on Cage (especially those non sequitur moments adding nothing but color) and Monroe conducting parallel investigations into his killer and her own past. The composition of the prologue adding to Longlegs' introduction is worth admission alone by really putting us into the shoes of a young girl—his main targets. And while both lose some luster in the expository dump of meaning that connects them to a much bigger picture, all the "Mr. Downstairs" and doll stuff is very cool mythologizing on their own when still in context with a deranged lunatic's deeds. It all adds up to a more than solid genre flick I didn't love but can definitely see why so many do.

- 8/10

Cinematic F-Bombs:

This week saw APOLLO 18 (2011), DREAMGIRLS (2006), and THE TOURIST (2010) added to the archive (cinematicfbombs.com).

Beyoncé dropping an f-bomb in DREAMGIRLS.

New Releases This Week:

(Review links where applicable)

Opening Buffalo-area theaters 1/3/25 -

THE DAMNED at AMC Market Arcade; Regal Elmwood, Galleria & Quaker

Streaming from 1/3/25 -

MOTHER’S INSTINCT [2024] – Hulu on 1/3

THE FRONT ROOM – Max on 1/3

UMJOLO: MY BEGINNING, MY END! – Netflix on 1/3

WALLACE & GROMIT: VENGEANCE MOST FOWL – Netflix on 1/3

“The script is full of hilarious sight gags as a fleet of evil Norbots hide its intentions to all those not looking as closely as Gromit (and us). The AI commentary is handled well too.” – Full thoughts at HHYS.

SONS OF ECSTASY – Max on 1/9

Now on VOD/Digital HD -

A REAL PAIN (12/31)

“Kudos to Eisenberg for finding the sensitivity to not only write this character with such depth of humanity, but also to reject easy answers or solutions for him.” – Full thoughts at HHYS.

WICKED (12/31)

Brief words at Letterboxd.