Here we are on December 15th with a slew of new independent Oscar contenders releasing (or already having been released) in NYC and LA, but WB’s WONKA is the only new title hitting Buffalo theaters (besides the usual Indian films and one screen for MAESTRO despite hitting Netflix in five days). That’s absolutely crazy.

Crazy due to the fact many such titles won’t come at all now. And crazy personally because it means getting access to them before my first vote is due becomes near impossible. Some studios want to hold their big contenders until the last possible second, sending them only after that deadline. We can’t nominate what we can’t see.

Huge kudos to those publicists that work to let Hollywood know this fact. We actually just got one sent at the last second last night to give us a couple days to consider it for Tuesday’s vote. Either way, the GWNYFCA nominations will be announced on 12/22 at 10am on Twitter and shortly thereafter on our website. I can’t wait to see what our collective choices are.

And, speaking of lists, The Film Stage just released their Top 50 Films of 2023 as compiled by an aggregate vote of contributors. It’s always a great resource for blind spots. I wrote a little something about two of my faves in HOW TO BLOW UP A PIPELINE (#33) and KNOCK AT THE CABIN (#41)—a tease of what will also eventually be included in my full Top Ten once I see a few more films this weekend (and probably next week if I can push it a little further).

What I Watched:

AMERICAN FICTION

(in limited release)

It's the dejection that allows Cord Jefferson's AMERICAN FICTION (adapted from Percival Everett's novel Erasure) to work. This satire isn't educating us. It's not calling something out and then presenting a solution. No, it's simply giving life to the fatigue of our unfortunate reality. It's making sure that while we laugh at the crazies, we must also cry with those who have no escape. Because that which reduces Black America into the base stereotypes white America's money deems palatable is increasingly the only choice Black America has for success.

That's not an easy tone to maneuver through. It's why John Ortiz's Arthur is crucial to the whole despite superficially just being the middleman that bridges the gap between lead Thelonious 'Monk' Ellison's (Jeffrey Wright) depressing reality and the even more depressing nightmare spawned by his unlikely triumph. Arthur is the facilitator. He understands what Monk stands for and agrees with those sentiments to the point of overtly mocking those who aren't "in" on the joke when Monk writes the very drivel he rails against as a serious "race-blind" novelist. But he also understands money and is willing to laugh his way to the bank.

Monk, however, is not. He'll debase his integrity to take the paycheck and be done with the charade, but he's ready to pull the plug the moment that charade snowballs out of control. Unfortunately, the momentum is no longer dictated by his wants and desires. Public consciousness takes the wheel and the market drives, rendering him nothing but a footnote to the commodity machine of what it has decided to exploit. So, now it's either go with the current or watch it pass. Because it won't stop. And anything he might say to try pumping the brakes will only light a different fire. The machine will make money off him regardless. The question is whether he'll take a cut.

Add the familial drama of disease, death, new beginnings, and tragic endings and it becomes difficult to excuse the allure of selling out. It's a question we ask ourselves each day: Why do the stupidest people seem to have all the wealth? The answer: Because they are stupid. Well, not stupid. Amoral. Yes, there's something to the film's message about "relating to people" too, but I think that is as much a satirical wink as the reduction of Black experience to salacious violence for white entertainment. Because Monk is correct in his thinking. He's right to be frustrated and against everything he finds himself doing. That shouldn't be swept under the rug as "being difficult."

I'd have liked the film to engage with that a little more because there is a bit of mixed messaging in that regard, but I don't think it ruins what otherwise works so well. Because most of the people who Monk "doesn't relate to" aren't amoral idiots. They simply want to be heard and not judged for enjoying something that might be problematic without context. It's why Issa Rae's Sintara Golden is as crucial as Arthur. She's another mirror for Monk, one that points back at him in the opposite way. Because where Monk is "better than" Arthur for knowing when to stop, he only thinks he's better than Sintara.

That dynamic is where we really see the complexity of the situation and how people like Monk can be as reductive as the lemmings who buy what Sintara admittedly wrote as a means to cater to their desires. That confusion is where the truth lies. That slippery slope where intelligence devolves into hollow sanctimony because Monk has stopped doing the work to see that some cultural changes in the relationship between art and commerce aren't as black and white as he believes. There needs to be a middle ground. It might not be ideal, but it can become the only avenue towards fixing the problem from the inside.

I could have done without the ending(s) even if it drives home the point. It's because it drives home that point so blatantly that I found it pandering. Except, of course, that the pandering is also the point. Those are the levels Jefferson and company are working on, though. You must embrace the clichés to challenge them, and, because of that inherent dejection, you must also center those clichés to reveal how tiring they are to those they harm. The annoyance is therefore the joke. Eradicating it is a futile endeavor. Minorities must instead evolve their mindsets to work within the racist system in ways that make its racism work for them.

- 8/10

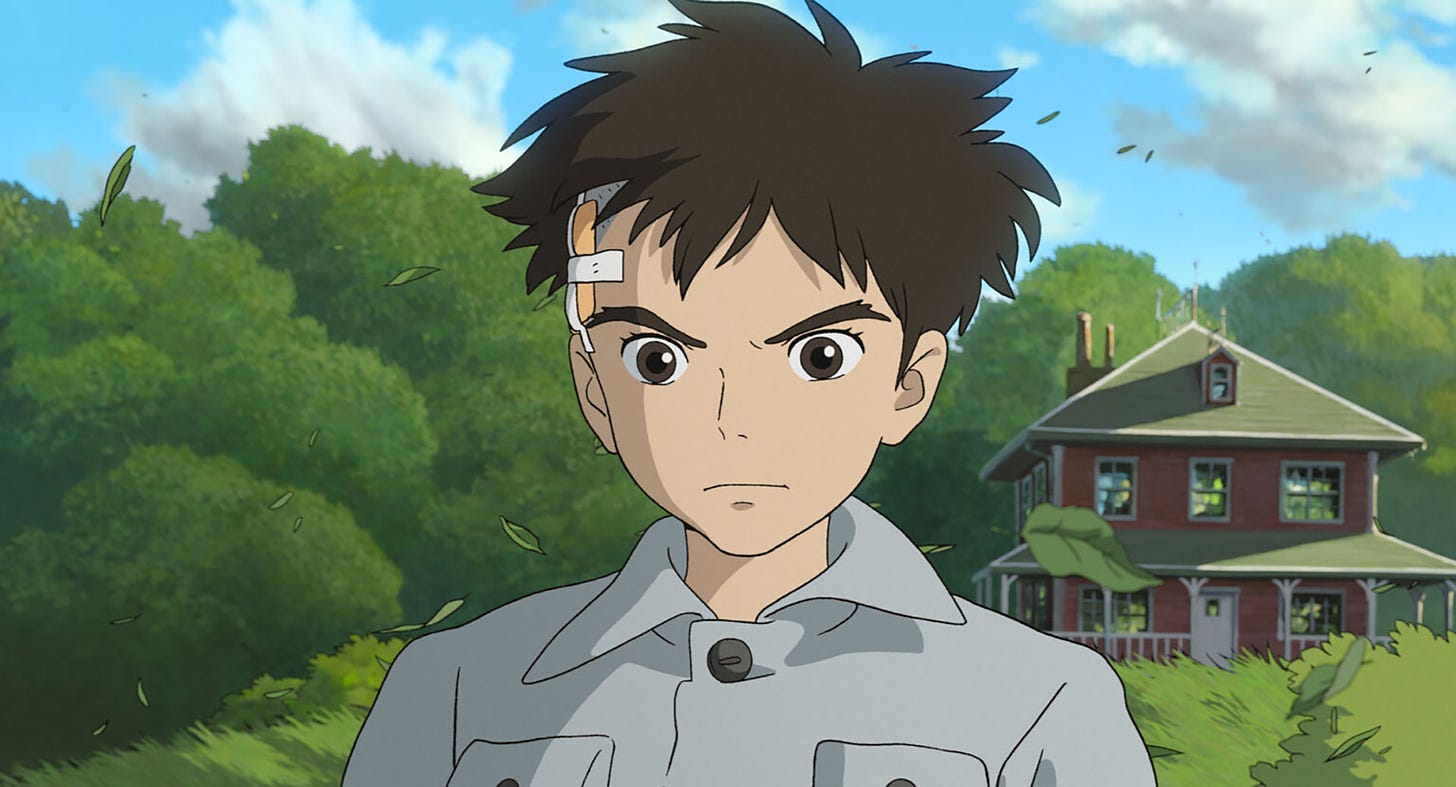

THE BOY AND THE HERON [Kimitachi wa dô ikiru ka]

(in theaters)

As death and destruction rain down upon Tokyo as a result of the Pacific War, Mahito Maki (Soma Santoki) is left struggling to find reason in the world. A hospital fire caused by the fighting takes the life of his mother, pushing his father (Takuya Kimura’s Shoichi) to move them to the countryside where his new fighter plane component factory has just opened a few years later. This new home is also where Mahito’s mother grew up … as well as where Mahito’s future stepmother—her younger sister Natsuko (Yoshino Kimura)—still resides.

Hayao Miyazaki’s THE BOY AND HERON is a semi-autobiographical fantasy adventure that mirrors the auteur’s own childhood feelings (and, presumably, his current ones on the potential cusp of retirement … again). It’s about escaping tragedy through one’s imagination and how the process of doing so can be both a powerful tool with which to move forward and a crutch with which to lose yourself even further. Because Mahito isn’t the first of his bloodline to be drawn towards a magical tower overgrown by forest. He might, however, be the last.

Accompanied by a gray heron (Masaki Suda voices the bird and the man who seemingly lives inside him—a character I will admit I still don’t fully understand since the film effortlessly cuts between him being friend and foe without any true motives or reasons for the shifts beyond what the plot demands), Mahito’s selfish curiosity is buoyed by the fact he’s also seen Natsuko disappear into the woods too. So, he sets out to find her, call the heron’s bluff that his mother might still be alive, and distract himself from his harsh and complicated reality.

What he finds is magical and absurd. A universe occupied by man-eating pelicans and giant parakeets presumably created by the so-called “Tower Master” (Shohei Hino). There’s also tiny blobs called Wara Wara who must feed on the few fish populating the water to blow-up like balloons and be reborn in the real world if the birds don’t consume them first. Enter living humans amongst the dead to help keep this ecosystem sustainable—humans that bear a striking resemblance to those Mahito already knows, albeit much younger and seemingly trapped beyond time.

How everything works together proves a lot as Miyazaki goes wild with his characters and sets to deliver visually stunning sequences that are just as perplexing narratively. Think of this tower as a “Wonderland” that morphs and distorts reality to be simultaneously scarier and safer than the conflict and emotions our young protagonist simply doesn’t have the means to process or reconcile on his own. It’s a sort of “Oz” in that way too considering others have traveled here before him to learn and evolve themselves before returning to life.

As such, it’s as much about young Mahito coming-of-age and accepting tragedy and discomfort as an unavoidable part of life that shouldn’t prevent him from embracing the good that also exists (regardless of how it might feel like a consolation prize or replacement for that which he’d rather have) as it is the “Tower Master” coming to grips with the fact that his utopian escape has gradually become just as violent and chaotic as the world he left. Does that mean his work was meaningless? Not necessarily. He just might have accomplished more trying to make reality better.

So, there’s a message for folks of all ages here. A paradise turned nightmare with some really jarring imagery that drives home the fact we cannot eradicate hardship simply by willing it. Because even if you do for yourself, that peace comes via the sacrifice of others. Someone must arrive to kill for those who can’t so they can survive. Someone must appear to protect another food source so that those consuming it don’t deplete it to the point of triggering their own extinction too. Maturity at any age is realizing conflict isn’t the problem. It’s our response to it.

- 8/10

THE DELINQUENTS [Los delincuentes]

(streaming on MUBI; Argentina’s International Oscar submission)

It’s a victimless crime … except, I guess, for the men committing it.

Morán (Daniel Elías) is sick of his job at the bank. So, when the opportunity presents itself to put a deposit in the safe without a co-worker accompanying him, he takes it. In his mind, the three-and-a-half-year jail sentence he assumes he’ll serve after turning himself in (and good behavior) is worth not having to spend another twenty-five in the doldrums of his day job to make the same money before retirement. Take only that amount. Hide it. And reclaim it upon release.

An accomplice is therefore necessary because he cannot be sure his hiding place will be secure unwatched. And since Román (Esteban Bigliardi) leaving work early that day provides him the opportunity to take the money, why not blackmail him into supplying that assistance? He’ll even give him the same amount of money for his trouble. An even split of $600,000+ for just keeping his mouth shut. Except, of course, that doing so is easier said than done once the absence that made him Morán’s target ultimately puts him in the bank’s crosshairs too.

Writer/director Rodrigo Moreno’s THE DELINQUENTS is thus one of the most mundane bank robberies in cinematic history precisely because his robbers are so mundane themselves. These are regular people devoid of any real aspirations. They simply embrace the routine of capitalism and try to stay awake while doing it. So, why wouldn’t their dreams be equally quaint? Rather than wealth or notoriety, they seek freedom from the grind. The irony is that they could have just quit their jobs and found this elusive independence without all the additional stress.

That’s where this quiet, three-hour comedy shines. Not the blatant dualities (real prison vs. prison of the mind, Germán De Silva playing two different “bosses” in both men’s lives, and an inevitable love triangle with Margarita Molfino’s Norma). Those are fun and provide the whole a nice clean, circuitous pathway forward towards a pitch-perfect farce of an ending, but the idea that it takes a crazy premise for both men to finally come alive is the real point. That which we all want is usually right in front of us. We’re often too comfortable within society’s patterns to ever take it.

- 7/10

DREAM SCENARIO

(in theaters)

It's a brilliant concept. Harmless, boring nobody Paul Matthews (Nicolas Cage) starts popping up in random people's dreams until he becomes the most recognizable face in the world. The dreamers all want a piece of his celebrity. Marketing agencies want to commodify his insane brand reach. He just wants to pivot the notoriety towards his academic career and publish that book he's never written. And then the dreams become nightmares.

I was a fan of writer/director Kristoffer Borgli's previous film SICK OF MYSELF and DREAM SCENARIO definitely shares DNA with its themes on fame in the digital age often trending towards warped, flash-in-the-pan phenomena that ultimately finds its volatile shelf-life won't just cause the benefactor to fade away from public consciousness. It will inevitably ensure that their image is destroyed to a point of no return.

It's all about that table turn. It's about hubris. Whereas the lead in SICK OF MYSELF is intentionally bringing this result upon herself, however, Paul is mostly an innocent bystander to his unfortunate plight. Does that change considering he starts to exploit it along with everyone else? Maybe. Maybe not. To me, however, saying it does render the eventual tonal shift an uninteresting evolution at a moment when the film should be capitalizing on the investment its audience has given this wild journey in hopes of a worthwhile payoff.

Cage is great in the role. He does everything he must for the concept to come to life. In my mind, however, the script does him no favors by seemingly getting confused about what it wants to say since it's saying it about a person who wields zero control. Are we wrong for pitying him then? Does he deserve what happens? To equate it to cancel culture makes it even more perplexing since doing so makes it seem people who should be canceled have been unjustly vilified.

So, maybe I'm missing the joke? I still had fun with the film; it just crashed into a brick wall right when it seemed like it was hitting its stride and preparing to deliver the punchline. There's some good stuff as far as public consciousness dictating reality rather than reality itself, though. As well showcasing the lengths we'll go to piggyback on another's success in ways that use their newfound clout despite previously believing they held no intellectual value.

But it all seems to flitter away in lieu of genre conventions, a sharp (albeit believable) left turn into science fiction, and an ending that wants us to think Paul Matthews was never worthy of happiness. That he lucked his way into what he did have and needed to be punished for daring to dream about more. Or maybe he’s being punished because he refused to actually work for it? I stopped caring.

- 6/10

EARTH MAMA

(streaming on Paramount+)

This isn’t Gia’s (Tia Nomore) first pregnancy. Too often we see this type of story centering on a young first-time mother who doesn’t know what to expect as the system fails her. The result is always harrowing, generally hopeful, and usually marked by its agenda—whichever way it falls for the filmmaker. So, having her lead character fully conscious of what’s coming proves a crucial piece to the objective lens writer/director Savanah Leaf is using on her debut feature EARTH MAMA. It’s not therefore about success or failure. It’s merely the reality that most of these scenarios fall somewhere in between.

We’re talking about circumstances that any mother struggles to overcome let alone a Black, twenty-four-year-old, single mother of two who only gets to visit her son and daughter for one hour a week due to them currently being in the foster system. The courts tell Gia to go through the rigorous program necessary to prove she’s fit to be a mother, but she needs to work to pay for the classes within. And without a support system (her drug dealing sister supplies a roof over her head, but not a lifestyle any judge would deem child-friendly) or the kids’ fathers in the picture, she’s caught in a never-ending cycle of disappointment.

What then are Gia’s choices? Risk everything by rolling the dice only to end up losing the baby she’s about to have along with the two she barely sees? Go against every bone in her body to put the baby up for adoption so she can focus on Trey and Shaynah? Buckle under the pressure of society, her best friend’s religious zealotry, and the surreal umbilical cord dreams she cannot shake by going back to the drugs that helped put her in this situation? Between her case worker toeing the bureaucratic line and her job at a department store photo studio throwing every form of “family” she doesn’t have in her face, trust and hope are non-existent.

Enter Miss Carmen (Erika Alexander)—a social worker who runs Gia’s classes with the empathy and understanding to not simply use hollow words. Enter Mel (Keta Price)—a potential friend who hangs out in front of Gia’s sister’s place. Are they genuine in their desire to help? Are their worries conditional? It’s tough to really know, especially as someone who’s done this twice and been let down by anyone and everyone who she thought she could rely on. How real is the family (Sharon Duncan-Brewster and Bokeem Woodbine) who wants to adopt the baby? It will take a leap of faith.

Faith and a wealth of unfortunate truths once the stress and uncertainty inevitably push Gia into corner after corner with dwindling options. You really feel for her because you know she loves her kids and would do anything for them in a perfect world. It’s a testament to Nomore’s performance that this fact shines through the temper, frustration, and defeat that often drives Gia’s decisions. At the end of the day, she’s fighting. But when you follow the rules and still get nowhere, staying positive becomes impossible. And one slip means going back to the beginning. Sometimes the toughest act amidst such futility becomes recognizing when to stop.

- 8/10

MONSTER [Kaibutsu]

(in limited release)

“Who’s the monster?”

It’s a phrase spoken often throughout Kore-eda Hirokazu’s MONSTER. A mother hears it spoken as a forlorn mantra of defeat. A child hears it as a battlecry for play. We hear it and don’t know quite what to think. And that’s the point. Screenwriter Yûji Sakamoto intentionally tells this story of a young boy named Minato (Soya Kurokawa) three times with vary degrees of detail augmented by each chapter’s specific vantage point. He sets our expectations with the desire to upend them. But will it be for better or worse?

Round one is through the eyes of Saori (Sakura Ando). She’s a single mom who passes by her son Minato whenever work and school allow. So, he is usually home first. Which means she is seeing things without context after the fact: hair in the sink, one shoe instead of a pair, etc. Add a growing malaise and a bandage on his ear and Saori can’t help but assume something terrible is going on. And when Minato corroborates those fears after finding him alone in the dark at an abandoned train yard, she makes a beeline for the school.

Round two centers Minato’s teacher Mr. Hori (Eita Nagayama). It’s easy to dislike him at first due to the accusations as well as rumors labeling him “immoral” for frequenting a hostess bar. He’s flippant and disingenuous when confronted by Saori and so we have no pity for him when his life starts falling apart … until, of course, we see that the facts aren’t quite what they seem. Hori is caught between not wanting to ruin a child’s future, not wanting to give the school a bad name, and maintaining his reputation. It’s a no-win situation.

Which leaves round three to Minato himself. It’s here that we discover the “monster” is nothing more than a manifestation of shame rather than malicious intent. Kore-eda and Sakamoto supply the clarity we need to understand the full picture and realize the pain and suffering so many on-screen have been experiencing due to a culture that demands certain truths and actions beyond the scope of an equation dictated by simple “right or wrong.” Accidents are made into death sentences. Love is made impure. Protection becomes a liability.

The human aspects are what shine due to wonderful child performances by Kurokawa and Hinata Hiiragi as his friend Yori and poignant turns by Ando, Nagayama, and Yûko Tanaka as the school’s principal. Each is operating from a level of compassion, but also from motives they aren’t always willing to divulge. It’s why the truth of Minato’s sorrow is so heart-breaking. This is a child listening to what the adults around him say without the necessary context that they are often saying them without thinking about the consequences society has worked so tirelessly to pretend don’t exist.

Even so, I really like the bureaucratic aspects too. So much of what occurs does because of the institution that’s simultaneously protecting and failing young Minato—often through the exact same actions. We’re talking about subject matter that too many are afraid to be vulnerable about and the resulting silence creating a snowball effect without end. One lie begets another. Manipulations abound and reductively restrictive rules cause the truth to be worse for the victim than deceit. That it surrounds two children struggling against the weight of the world despite just wanting to laugh makes it all the more tragic.

- 8/10

ORIGIN

(playing in NYC/LA; limited release on 1/19)

Rather than create a documentary based on Isabel Wilkerson’s book CASTE or a straight biopic on the Pulitzer Prize-winning writer, Ava DuVernay decided to do both. ORIGIN is therefore a way into the material by dramatizing the journey Wilkerson took to find, research, and articulate it. How did the idea for the book arrive? (A pitch from her former editor to cover the Trayvon Martin murder.) How did caste’s connections and separations from racism pop into her mind? (Conversations with her Black mother and white husband.) We’re experiencing Isabel’s enlightenment right as she in turn enlightens us.

It’s an ingenious approach to simultaneously educate and entertain. Some of it works better than the rest (moments when other characters teach or debate feel very heavy-handed by virtue of distilling what was probably hours of dialogue into a few concise lines stripped of all organic spontaneity), but you cannot deny the power of the whole when those more lecture hall passages are put into context with the authentic human drama of the rest. Because there’s a lot of pain and loss on-screen that spans decades. It might not all be the same, but a through line is shared.

The non-fiction reenactments are crucial to breathing life into those more academic scenes of voiceover where Wilkerson (beautifully played by Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor) starts drawing her lines between slavery, the Holocaust, and Indian Dalits. There’s Allison and Elizabeth Davis (Isha Blaaker and Jasmine Cephas Jones) infiltrating the Jim Crow south as clandestine investigative journalists. August Landmesser (Finn Wittrock) and Irma Eckler’s (Victoria Pedretti) forbidden love in Nazi Germany. And Dr. Bhimrao Ambedkar (Gaurav J. Pathania), a Dalit hero whose statues are caged so as to ward off vandalism from higher castes.

To watch them—even from a distance as teaching tools more than characters—is to help understand the lessons of their lives. They also work to circle back to Wilkerson herself and her career as a journalist, marriage to a white man (Jon Bernthal’s Brett), and proximity to both white and Black cultural institutions via generational and professional avenues. How does she navigate the overlap? How can she get her mother (Emily Yancy) and cousin (Niecy Nash) to understand racism is a product of this larger issue of caste? How does she get a MAGA plumber (Nick Offerman) to see her inherent humanity above her skin color?

Your enjoyment might hinge on your tastes where it comes to cinema as a result. There are some very “documentary-style” scenes where Isabel is interviewing people (Audra McDonald’s Miss Hale or a man who played little league with Al Bright) or coming to an academic epiphany by way of explaining to a friend. Some might find them jarring when compared to Wilkerson’s own trajectory as a woman watching everyone she loves die, but it does all fit together. It speaks to giving voice to experiences and evolving to reinterpret them through a new lens.

In the end it’s all really about empathy and power. It’s Wilkerson using her personal narrative to point out the ways in which so much of the hate in this world is predicated on man-made conventions of manufactured superiority for the benefit of the ruling class’s continued prosperity regardless of how those conventions are ultimately carried out. Until we open our eyes and understand that we are all human and thus worthy of dignity, this millennia-old cycle of oppression and systemic compartmentalization will never cease to be.

- 8/10

THE ZONE OF INTEREST

(in limited release)

The plot is simple: A happy family of five that lives comfortably next door to Dad’s place of business is about to be uprooted upon learning of a promotion and transfer that will take them miles away from the home they’ve made these past four years. It’s an easy dramatic scenario to picture. You may have lived it yourself. Except for the wrinkle that he’s a Nazi commandant and the noise we hear from the other side of the garden wall is the screaming of Jewish prisoners at Auschwitz.

Not the subject matter you would think to want to write around and yet that’s exactly what filmmaker Jonathan Glazer does with his adaptation of Martin Amis’ novel THE ZONE OF INTEREST. Less a literal translation and more tonal sibling to the source, he knew bringing such charged material to life in a way that didn’t make it obscene would be a challenge. Because you can’t humanize these characters with sympathy or just make the whole another Holocaust trigger warning for survivors. So, he made sure it would be about us instead.

By stripping away all emotion from the craft itself, Glazer presents an objective lensing of a moment in time for a family that looks and acts like so many when removed from the heinousness of this specific reality. He uses surveillance style camera set-ups to statically capture his actors in long takes depicting mostly mundane activities and improvised conversations, cross-cutting together each room to supply an overall sense of their existence via an almost faux documentary aesthetic. These are the motions of life—the arguments and jokes that seem innocuous until context can no longer be ignored.

That’s where its power to disturb lies. Not just with you acknowledging the horrific similarities to your own day-to-day, but also the characters on-screen numbing themselves to the truth with varying degrees of success. It doesn’t get better than with Hedwig Höss’ (Sandra Hüller) mother smiling and praising her daughter for marrying well and living a dream one day to growing physically and emotionally ill from the sounds and smells of what’s happening the next. Going from joking about her former employer burning to death to fleeing without a word in the night concisely portrays the slippery slope of complicity.

Then there’s the constant animal-loving dynamic Rudolf Höss (Christian Friedel) has with dogs throughout. There’s no more blatant analogy than watching him treat a pet with such unadulterated respect and dignity before hearing him order a human prisoner he surely calls an “animal” to be drowned a few scenes later. Everything from Mom trying on a new fur coat to one of her sons looking at his “geology” collection takes on a malicious tone upon considering the full picture. It should make even the strongest stomach risk losing their popcorn.

So, while it’s not a horror film per se, you can’t avoid the sense of uneasiness permeating each frame. Whether the smoke of chimneys and trains, bath time after swimming in a river suffering from camp “runoff”, or the turn-on-a-dime mood swings Hüller effortlessly pulls off to make her Hedwig more monster than Rudolf, the discomfort lingers long after the credits end. Especially now considering the US just vetoed another UN resolution for a cease-fire as Israel commits genocide on the people of Palestinian. Does our country also puke in the stairwell before returning to its complicity? Or does it sleep like a baby?

You must give Glazer and cinematographer Lukasz Zal a ton of credit for really capturing this story in a methodically unfeeling way wherein its atrocities (seen and unseen) occur in the background. Young love. Slave labor. Night vision scenes of a girl depositing food where prisoners will be working. A home being worth more than thousands upon thousands of lives. Through it all, the only real emotional outburst lies in Hedwig’s refusal to relinquish her “perfect” white picket fence utopia. A soulless creature in an Eden covered by the ashes of innocents.

- 9/10

Cinematic F-Bombs:

No new additions to the archive this week, so here’s John McEnroe going wild in MR. DEEDS. cinematicfbombs.com

New Releases This Week:

(Review links where applicable)

Opening Buffalo-area theaters 12/15/23 -

JORUGAA HUSHARUGAA at Regal Elmwood

MAESTRO at Dipson Amherst

“Mulligan and Cooper are too good for it not to be [enthralling]. Maybe it is all style and little substance, but its dual portrait (albeit shallow) is no less invigorating as a result.” – Full thoughts at HHYS.

PINDAM at Regal Elmwood

WONKA at Dipson McKinley, Flix & Capitol; AMC Maple Ridge & Market Arcade; Elmwood, Transit, Galleria & Quaker Regals

Streaming from 12/15/23 -

CHICKEN RUN: DAWN OF THE NUGGET – Netflix on 12/15

FACE TO FACE WITH ETA: CONVERSATIONS WITH A TERRORIST – Netflix on 12/15

FAMILIA – Netflix on 12/15

FINESTKIND – Paramount+ on 12/15

“There's no better Father's Day gift than streaming an example of their stunted emotions and stubborn failures via a thriller-adjacent plot that ultimately lets them off the hook to rousing fanfare.” – Full thoughts at The Film Stage.

THE DELINQUENTS – MUBI on 12/15

Thoughts are above

THE FAMILY PLAN – AppleTV+ on 12/15

JOYLAND – Criterion Channel on 12/19

“JOYLAND ultimately proves itself to be about complicity. The ways in which our silence allows for the systematic dismantling of another's chance to be free.” – Full thoughts at HHYS.

DANIEL – Max on 12/20

MAESTRO – Netflix on 12/20

“Mulligan and Cooper are too good for it not to be [enthralling]. Maybe it is all style and little substance, but its dual portrait (albeit shallow) is no less invigorating as a result.” – Full thoughts at HHYS.

DR. DEATH: CUTTHROAT CONMAN – Peacock on 12/21

Now on VOD/Digital HD -

CRAIG BEFORE THE CREEK: AN ORIGINAL MOVIE (12/11)

DIVINITY (12/12)

“DIVINITY will not be something you can soon forget. It's not action-packed, but it's never boring. Not if you open yourself to its themes of awakening.” – Full thoughts at HHYS.

IMMEDIATE FAMILY (12/12)

UNDER THE INFLUENCER (12/12)

“The third act is a super earnest fantasy that ensures the movie’s messaging is blatantly expressed for those who weren’t paying attention, but it’s also quite charming and hopeful in its homage of BEFORE SUNSET sentimentality.” – Full thoughts at HHYS.

WALDEN (12/12)

TAYLOR SWIFT: THE ERAS TOUR (12/13)

SHELTER IN SOLITUDE (12/14)

THE DELINQUENTS (12/15)

Thoughts are above.

PRISCILLA (12/15)

“I think Coppola does well balancing that duality, never shying from the violence or the romance. If anything, she employs that convergence to deliver a compelling biopic that seeks to dismantle the illusion by recreating its inescapable allure.” – Full thoughts at HHYS.

RUTHLESS (12/15)