Finished the 2023 edition of Fantasia Festival with fifteen titles of varying success (only two really didn’t work for me). RIVER was my favorite. APORIA and WITH LOVE AND A MAJOR ORGAN follow closely behind. All in all another great dive into genre films with a festival that never disappoints.

I also finally caught up to OPPENHEIMER: a great feat, albeit probably not a Top Ten feature for me. Figured it’d be the first of the BARBENHEIMER behemoth to be pulled from screens due to its runtime. So, here’s hoping I can catch BARBIE in the next couple weeks too.

Time will be tight, though, as TIFF is coming right around the corner. Already received my first screener despite the full schedule not being released until 8/15.

What I Watched:

LOVE LIFE

(now in limited release)

When tragedy strikes the Osawa family on a day marked for celebration, neither Taeko (Fumino Kimura) nor Jirô (Kento Nagayama) quite knows what to do. They should be able to grieve together. They should be able to look into each other’s eyes. And yet they simply stare off into the distance, going through motions as numb, hollow husks searching for some sign of life while trying to avoid showing too much.

Because it’s difficult to know exactly where they stand. Despite being married for a year now, they still find themselves at a distance due to the circumstances surrounding their relationship. Taeko was married once before and had a six-year-old son (Tetta Shimada’s Keita) before Park (Atom Sunada) ran away. Jirô was engaged (to Hirona Yamazaki’s Yamazaki) when he began his affair with her. Add the fact that his parents (Misuzu Kanno’s Myoe and, especially, Tomorô Taguchi’s Makoto) can’t quite wrap their heads around their son marrying a divorcee and forcing them to be grandparents to a grandchild that “isn’t theirs” and you can begin to see how fragile things already were.

In another filmmaker’s hands, LOVE LIFE would probably be full of fireworks as this married couple comes to grips with what happened by distancing themselves even further while moving closer to those former loves from their pasts. This would probably be the case if it was set in many places besides Japan too. But that’s what makes Kôji Fukada’s drama so powerful. The silences where steely frustrations and unavoidable embarrassment are left unsaid really speak to the struggle these characters face moving forward. Because everything intimated and refuted about their love does exist. And how they react to those truths could shatter everything they’ve built.

So, don’t expect things to get blown out of proportion. Don’t assume Park or Yamazaki are going to use the situation to get back together with Taeko and Jirô respectively. Jealousy isn’t what Fukada is interested in pursuing. He’s focusing upon forgiveness instead. Not for the other’s transgressions or unspoken feelings, but for themselves. Can Taeko forgive herself for stopping to look for Park? Can Jirô forgive himself for breaking Yamazaki’s heart? Can their shared nightmarish plight get Makoto and Myoe to finally realize the pettiness of their cold shoulder to support the family given to them rather than lament the loss of the one they always wanted?

And there’s the need to forgive themselves for the spark to this emotional upheaval. Taeko blames herself. Jirô feels guilty for selfishly breathing a sigh of relief when he should have been mourning. The circumstances are obviously heightened, but the result is a resonant and universal sense of what living with and loving someone else entails. It’s never easy. It’s always complicated. And you will ultimately make mistakes. But the thing you cannot do is run from the inevitable fallout or avoid the truths that exist in your heart. Because it’s not about what you did to let shame prevent you from looking your partner in the eyes. It’s about looking there anyway.

Kimura shines in the lead role. Her strength to call out Jirô’s father when he goes too far or push Park for answers when he suddenly comes back into her life mixes with a justified anger for having to deal with both at all that provides a palpable baseline for who she is and the decisions she’ll soon make. Because Taeko will do anything for the people she loves. She doesn’t absorb these slights for herself, but to protect those who are inevitably caught in the crossfire through no fault of their own (Keita as a symbol of her former marriage, Park as a deaf Korean immigrant, etc.). It’s a commendable feature of her love and an unfortunate opening that leaves her vulnerable.

The film is a series of events wherein Taeko and Jirô are let down by each other and themselves. It’s about the ways in which they contort themselves so as not to actually talk about what has happened or what they’re truly feeling—leaving them susceptible to being hurt further by the need to fill in the blanks, conjuring their own assumptions instead. They turn away rather than towards to confront their fears elsewhere, leaving their genuine love in a purgatory that may never relinquish it. The question is therefore whether they can remember they’re no longer alone.

- 8/10

OPPENHEIMER

(in theaters)

It’s a tale of two trials. Except, of course, that neither half is a trial—a fact those presiding over both events are quick to stipulate whenever the accused (or party at threat of being “denied”) dares to call their tactics out for being unjust. One sees J. Robert Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy) appealing the revocation of his security clearance years after stewarding the invention of the atomic bomb. The other finds Admiral Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey Jr.) seeking a cabinet appointment. Both prove that even the most cautiously optimistic belief that any nation on Earth might handle the responsibility of nuclear power was simply naïveté.

That’s what Christopher Nolan’s OPPENHEIMER (adapted from the book American Prometheus by Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin) is really about. Not how the titular character changed the world in Los Alamos. Not his life as a womanizing prophet of theoretical quantum physics. No, it’s about the reality that the bomb was a symptom (albeit much more than that to those impacted at Hiroshima and Nagasaki) of the prevailing international military industrial complex rather than its catalyst. What should have been a deterrent to war merely became the next tool to ensure we’d never see a period of time without a war raging again.

It’s a sobering thought that ultimately haunts Oppenheimer from the moment we first meet him out of time. There he is as a student at Princeton, unable to sleep with the sound and fury of death and destruction roiling through his brain. There he is at a table in a tiny room being grilled by an over-zealous prosecutor (Jason Clarke’s Roger Robb) at the behest of an “impartial” tribunal, unable to fully hear his words above the sensorial overload of terror for what his science wrought. But none of that is present to earn sympathy from us or to prove an admission of guilt. It’s a deflection from what’s really going on. A reminder that intent is meaningless in the face of ambition.

Because the truth of what Nolan weaves through flashbacks sparked by the testimonies of both Oppenheimer and Strauss is that it’s all been a game. Those who believe themselves to be in control are merely puppets for the ones who are. The difference is that Oppenheimer acknowledges this fact. He knows Admiral Groves (Matt Damon) picked him because he was a liability. Because he had everything to lose and thus one hand perpetually tied behind his back. He may have been arrogant, but he wasn’t vain. Not like Strauss—a man so wrapped up in the strings he’s pulling that he forgets about the ones tightly affixed to his own wrists.

At three hours long, however, we aren’t able to fully grasp this notion until we’re already two-thirds of the way through thanks to “surprise” revelations that prove cuter than they do profound. Does shielding the real reason Nolan has chosen these mirrored “trials” add anything to the whole? No. The impact of what we watch beforehand doesn’t grow out of the reveal. Only the impact of what follows does. So, why not play it straight from the beginning? Why toy with the audience’s expectations? Because that which does follow pales in comparison to the rest. It serves to create a villain. And, in so doing, removes us from the weight of Oppenheimer’s grief to enjoy a romp of karmic “justice” instead.

Don’t get me wrong, though. Downey Jr. is absolutely fantastic and I love his more direct plot line to an eventual comeuppance. I’m just not sure it doesn’t take away from the potency of the more introspective and esoteric Prometheus tale at the film’s center. That’s why I must step back and view the whole as being about more than these men. To see Nolan’s goal as proving they were both pawns to a changing tide of bloodlust and tribalism wherein World War II became less about finding allies to fight for a common cause and more about aligning with enemies to cheat, steal, and cut loose once the bigger threat to both was defeated.

That’s where the communist angle comes in and why all those tertiary characters (including Florence Pugh drastically underused Jean Tatlock) must be introduced despite being throwaways who cannot earn the emotional gut-punch Nolan wishes they can. Jean, the Chevaliers, even Oppenheimer’s brother are pawns to his story like he’s a pawn to that of the United States’ demand for supremacy. It all becomes fodder for Roger Rob to wield as Ludwig Göransson’s score ramps up to climax. So much so that even the wonderful scene where he gets taken to task by Emily Blunt’s Kitty (an actor elevating another weakly written prop to almost feel real) becomes a victim to Nolan’s too-smart-for-his-own-good shell game.

Thankfully, despite my qualms with Nolan purposefully structuring things to exploit our belief he’s finally told a straightforward story, I was still completely taken by its gravitas. Give Murphy and Downey Jr. Oscars. Check my blood pressure after the latest PTSD-fueled flashback hits Oppenheimer while he attempts to be what is wanted of him even as he wishes to retreat. Bask in the narrative parallels by looking back to see where the manipulations were coming from even if the need to do so feels unnecessarily convoluted.

Much like my reaction to Paul Thomas' Anderson’s THERE WILL BE BLOOD, OPPENHEIMER is objectively a monumental work by an artist at the peak of his ability. I just prefer Nolan’s messier swings wherein heart and excitement trump his obvious technical prowess.

- 8/10

Fantasia International Film Festival

HUNDREDS OF BEAVERS

(Canadian premiere)

Ryland Brickson Cole Tews and Mike Cheslik’s LAKE MICHIGAN MONSTER earned its cult following with a DIY aesthetic and madcap absurdity that I respected more than I enjoyed. It was fun. A title I’d recommend being seen by those who already have an inclination rather than one I’d enthusiastically demand be viewed sight unseen.

So, I won’t lie and say I didn’t approach their follow-up HUNDREDS OF BEAVERS with slight trepidation. Or that my discovering it was a whooping 108-minutes long didn’t make me cringe at the thought of going comatose once the joke went stale. But while this live-action LOONEY TUNES epic of silent-era slapstick nonsense is definitely too long (I admittedly took a critical break around the hour mark), it proves itself to be a vast improvement over its predecessor by fully leaning into the madness until you can’t help reveling in its charm.

The story follows a hapless apple whiskey purveyor named Jean Kayak (Tews) who gets too sloshed on his own wares to realize an influx of beavers have been munching on every piece of wood in the forest. Fast-forward to the third verse of the opening song and Jean finds himself destitute and dry in the freezing cold, his apple trees and distillery burnt to a crisp.

A few circuitous gags later, whereby he attempts to keep warm and find food, puts Jean onto the trail of a master trapper (Wes Tank), a cantankerous shopkeeper (Doug Mancheski), his furrier daughter (Olivia Graves), and a native trader (Luis Rico). Gleaning what he can from their comings and goings, he eventually becomes a trapper himself with dreams of killing enough rabbits, beavers, and wolves to buy a good coat, get his own rifle, and marry the only woman in this war zone of conniving creatures regardless of her father loathing his very existence.

Cheslik (who directs) and Tews (who co-writes with him) pretty much put forth a series of skits wherein Jean is brutalized by his would-be animal victims in ways that teach him how to later brutalize them instead. He uses that unintentional education to lay the foundation for a Rube Goldberg-esque master plan of food pyramid violence that he knows can win him his prize. And all the while the beavers continue building a bunker that houses dastardly plans of their own.

It’s a humorous ride in lo-fi yet impeccably crafted compositing between live action and animation for quick-witted Roadrunner and Wile E. Coyote action—with a few Bugs Bunny versus Elmer Fudd shenanigans thrown in. Mostly silent besides grunting, the scenes between humans (namely Jean, the Furrier, and her father) homage Chaplin/Keaton antics while the decision to have all the animals played by people in mascot costumes lends a surreally inspired dynamic of nightmarishly comic proportions.

That it all leads to a finale you cannot even begin to imagine is both its best and worst feature. Because despite it making the ride worth any pacing bumps, it also reveals just how berserk things could have gone much, much sooner. Yes, the ways in which Jean and the animals attack each other escalate in their idiocy as time passes. But it’s still just them trying/failing to kill each other again and again.

Those first two-thirds desperately need more variety and WTF details like a Beaver Sherlock and Watson. Setting up what’s coming with intent (and a much defter hand than you might assume while watching) only matters if your audience remains awake for the payoff. If not for my makeshift intermission, I might not have been. But I’m glad I was since its conclusion really is unforgettable.

- 7/10

NEW LIFE

(world premiere)

Elsa (Sonya Walger) has ALS. Diagnosed six months ago, her symptoms have reached the point of affecting her job—a job that’s intentionally shrouded in secrecy at the start of John Rosman’s NEW LIFE. We glean details (sparse apartment, handgun, and Tony Amendola’s mysterious handler Raymond visiting with a new assignment), though, and conclude she’s either a CIA operative or assassin despite it not really mattering. It should matter. The fact it doesn’t is the main reason I could never let the story wash over me and the core of why it fails to live up to its potential.

Because although the movie is very much Elsa’s story, she isn’t the “lead.” She’s neither the first person we meet nor the presumed protagonist. We are conversely conditioned to hope she fails. So, suddenly pushing her into the “hero” role halfway through ultimately destroyed what was left of my good will. Not because she shouldn’t be the hero or that her trajectory doesn’t illustrate the overall message Rosman is trying to convey, but because he undercuts the effectiveness and necessity of both to facilitate an empty twist.

We meet Jessica (Hayley Erin) first instead. Distraught, covered in blood, and running for her life towards home. She washes up, finds a change of clothes, and discovers the engagement ring her boyfriend never gave her before realizing two men with guns have entered the house. Escaping through a window she finds herself stowing away in the backs of strangers’ cars, eventually meeting a kindly older couple willing to help.

The assumption we make (as well as anyone who encounters her and her black eye) is that Jessica is on the run from violence. That she cannot divulge too many details because trusting the wrong person could be the difference between life and death. Add Elsa’s activation on her crosscut parallel pursuit and we presume it’s true. Jessica either did something or saw something that a deep-pocketed entity can’t let become public knowledge. So, she becomes our focus. She becomes the character we pull for regardless of Elsa’s own tragic backstory. Flipping the script doesn’t therefore excite us. It frustrates.

I don’t want to give too much away, so I’ll try to keep plot specifics to a minimum beyond admitting Jessica is a MacGuffin. It doesn’t matter that we spend two-thirds of the runtime following her isolated path or that the film asks us to sympathize with her plight. Her true purpose is to set Elsa’s wheels in motion. How can you not then wonder what might have been if Rosman simply let that be the case?

What if he wrote this script as Elsa’s story wherein Jessica is merely her current case instead of pretending as though her existence is on the same level of importance first? I don’t think it fundamentally changes a thing when looking back with hindsight. Maybe the first half isn’t as mysterious as it is now, but the second half wouldn’t be nearly as manipulative either. Because we would know where we stand with the characters. We would give Elsa our weight and Jessica our pity. The latter can still have pathos. Her progress can still be about not taking life for granted. It would simply transparently do so for the benefit of the former.

Because we also don’t know what movie we’re in due to the subterfuge. Not truly. NEW LIFE’s start and finish are on completely different wavelengths. Yes, it’s cool and superficially effective, but it proves to be for naught the second that shift undermines the overall package. It’s too bad too since the much more horror-infused second half is memorable in its thrills and special effects. It’s also a shame because Walger delivers a fantastic performance that deserves more time and intent to let its third act revelations breathe and earn its emotional gravitas—gravitas the filmmaking thinks it has already.

I get the desire to make things more complex and twisty, but the script needs to be airtight for such devices to truly excel. It can’t make you feel as though it led you on only to provide a “gotcha” that renders more of what we’ve seen inconsequential than it augments. There’s an intriguing concept here as far as using the idea that ALS is like being a prisoner in one’s own body. That’s a thought that justifiably conjures fear, especially for those who don’t need to accept the reality themselves. I just think the finished product uses it as a gimmick rather than a lesson.

- 5/10

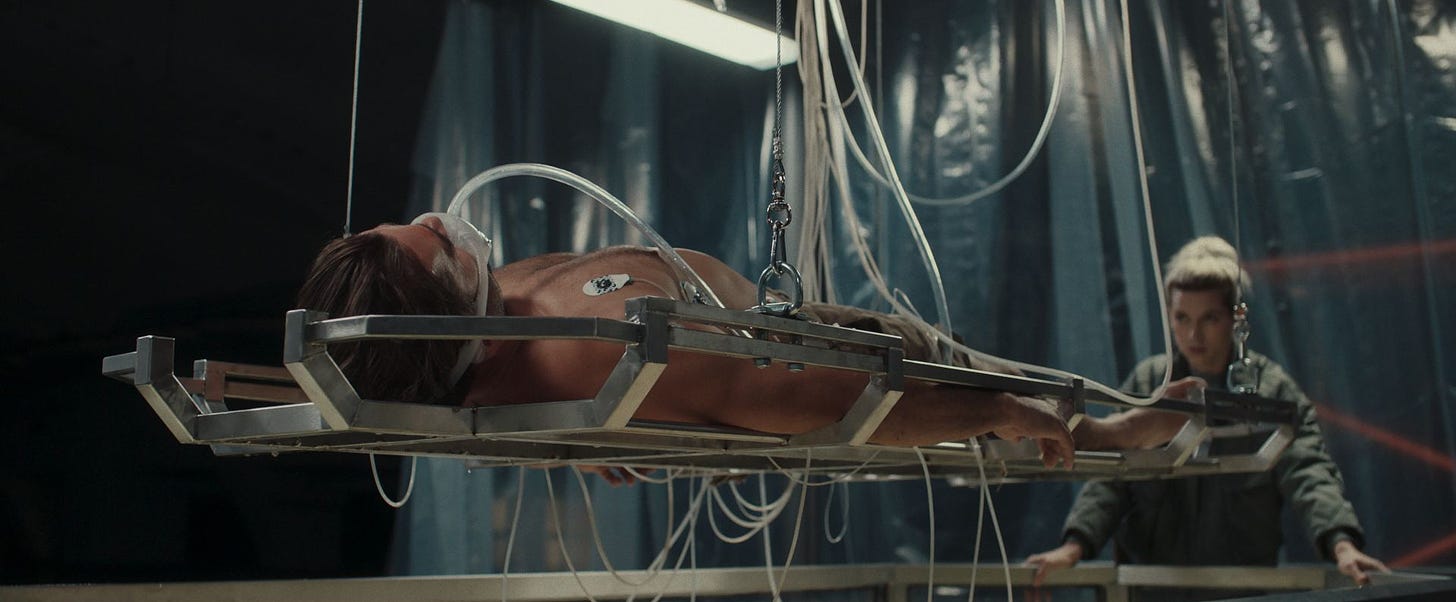

RESTORE POINT [Bod obnovy]

(North American premiere)

As the current climate evolves into increased violence, the future setting of Robert Hloz’s RESTORE POINT delivers a solution. It’s a technology that provides a way to revive those whose time to die was forced upon them by another. As long as you remember to download a back-up of your consciousness and memories, the taxpayer-funded institute led by Dr. Rohan (Karel Dobrý) can bring you back. His machine restores your body of its wounds before uploading your save file, allowing you to continue your life with nothing but a few hours of blank space.

The crucial catch to screenwriters Tomislav Cecka and Zdenek Jecelin’s plot is that Rohan cannot legally use any back-ups more than forty-eight-hours old. That’s the cutoff point for “rejection.” Think of the raw data of your mind as an organ being transplanted into your body. It will always be younger than its host and thus an anomalous intrusion to be fought against. So, you must be diligent. You must always remember to upload just in case. And don’t forget: one person’s grace period to allow themselves the oft bout of forgetfulness (or laziness) is another’s loophole. Those forty-eight hours separate salvation from absolute death.

We learn about this duality from a lone wolf detective who knows it all too well. Em Trochinowska’s (Andrea Mohylová) husband was killed by a terrorist organization seeking to free humanity from the prison of state-sanctioned immortality. Known as the River of Life, the group murders innocents to prove a counter-intuitive point whereby it instills the fear that no one is safe while also bolstering the importance of Kohan’s work—enough for him to take the company private as a means of “advancing their mission” (increasing profits). Unlike past attacks, however, they’ve finally caught their mistake. Rather than let their work be erased, they now only pull the trigger after their victim’s copy expires.

A web of intrigue stemming from Rohan’s chief scientist David Kurlstat (Matěj Hádek) and his wife being the latest “martyrs” ensues as Em once again hopes to use the hunt for a killer to single-handedly stop River of Life completely. It’s precisely this drive to shirk the rules for a personal agenda that endears her to untrustworthy figures and not those protected by said rules. Enter an illegal copy of Kurlstat (missing the six months of memories leading to his death), a suspected terrorist (Milan Ondrík’s Viktor), and a cavalier Europol agent (Václav Neužil’s Mansfield), each leading to more and more secrets that blur the line between good and evil where it comes to wealth and God-complexes.

There’s ample lore to work through as far as understanding the overall world on-screen, but it’s so close to our own capitalist wasteland that catching the drift shouldn’t be difficult. The dynamic built between this technology and how it fits into a social hierarchy fueled by profit is similarly easy to comprehend. That means we can devote our energy to getting to the bottom of the more specific mystery. Who benefits most from a group like River of Life? Why is Viktor willing to turn himself in as long as he’s guaranteed a “fair trial”? The answers to these questions are hardly unique, but the journey towards proving them never ceases to entertain.

A lot of that has do to with a solid lead turn from Mohylová—ever cautious and skeptical enough to tread lightly with the often-overwrought characters surrounding her. But there’s also the fantastic production design that truly excels beyond obvious budgetary limitations as ingenious art direction expertly turns contemporary items futuristic in lieu of fabricating everything fresh. This is apparently Czechia’s first sci-fi feature in forty years and thus a testament to everyone involved that it proves a worthy return to the genre. It may feel by-the-numbers in scope, but its execution more than makes up the difference.

- 7/10

RIVER

(North American premiere)

The last departure of the day has driven away, leaving the employees of Kibune, Kyoto’s Japanese Inn "Fujiya" with a break before that evening’s new arrivals. Two guests (Gôta Ishida’s Kusumi and Masashi Suwa’s Nomiya) start enjoying a meal. Another hits the hot baths (Haruki Nakagawa’s agent Sugiyama) while his novelist Obata (Yoshimasa Kondô) anxiously attempts to shake writer’s block. Taku (Yûki Torigoe), the establishment’s youngest chef, naps while his seniors (Kohei Morooka’s Morioka and Yoshifumi Sakai’s Eiji) prepare dinner. And Mikoto (Riko Fujitani), Kohachi (Munenori Nagano), and Chino (Saori) continue their shifts.

Unfortunately, they all also suddenly find themselves back where they were two minutes prior without warning or explanation. Just chaos. Because chaos is what occurs when a sprawling group of people find themselves stuck in an unexplainable temporal phenomenon. Mikoto and her coworkers catch on quickly because they’re forced to redo menial tasks that render the rewind indisputable. Kusumi and Nomiya need a bit more handholding since the only change they’re seeing right away is the fact the rice they just ate returned to their bowls.

Director Junta Yamaguchi and screenwriter Makoto Ueda (who were also behind the equally ingenious time-travel film BEYOND THE INFINITE TWO MINUTES with most of the same cast as part of the Europe Kikaku collective), meticulously go room to room by way of Mikoto’s vantage point as lead to lay the groundwork for their latest RIVER. She becomes the focal point as every two-minute segment’s fade to black reopens with her standing by the water before turning around to help put out whatever fire has inevitably erupted since.

First she and Kohachi realize what’s happening. Then they fill in Chino and their boss Shiraki (Masahiro Kuroki). From there it’s Kusumi and Nomiya. Then Obata (who is simultaneously overjoyed at the prospect of ignoring his deadline and curious about the experiences this consequence-free purgatory affords his imagination); Sugiyama (half-naked and desperate to escape the sauna), and Taku (finally waking to the fact the same song has been repeating itself over and over).

Add characters who must figure things out themselves (Eiji is a science major who takes it upon himself to discover the time loop’s source and return to normalcy; Kazunari Tosa’s hunter; and Shiori Kubo’s outsider stranded as a result of her vehicle having a frozen engine) and events can’t help spiraling out of control. All the extra time causes everyone to say things they might not normally say—clearing the air and confusing it at the same time. Suddenly they begin to wonder if they are the cause. Idle wishes and prayers to the Gods for love, inspiration, and salvation sharing a common solution: more time.

While the journey doesn’t utilize a single-take device like BEYOND, its frenetic pace and potential for extreme emotions (the kind that conjure laughter as much as fear once things reach the point of suicidal thoughts—a time loop staple) demands a similar level of investment that you’ll be more than willing to provide due to its infectious sense of entertainment. The filmmakers know exactly when to pivot from exposition to dramatics to climactic puzzle-solving, never letting us get tired by one aspect or the other.

We want to learn about what’s happening alongside these characters while watching how they unravel in response to the ordeal. We want to embrace Mikoto’s unbridled excitement during a wild yet heartfelt second act that gives her control of the narrative to deliver a necessary dream while igniting a nightmare. And we do want there to be a way out regardless of whether it comes as a byproduct of that which we already know or a completely new development in the eleventh hour.

When you have a stable of eccentric characters willing to feed into the genre’s stereotypical clichés so Mikoto can travel her own path without them distracting from her own personal progression, it’s easy to get lost in the moment so her highs and lows hit with maximum potency. And yet we still care about the others since the changing world (snow appears and disappears depending on which “world line” the latest reset landed upon) brings their desires into clearer focus too.

We could all use a breather to escape our own heads and realize nothing is quite as dire as it may initially seem.

- 8/10

Cinematic F-Bombs:

This week saw ANOTHER YEAR (2010), ARRIVAL (2016), BOOK CLUB: THE NEXT CHAPTER (2023), FUN WITH DICK AND JANE (2005), GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY VOL. 3 (2023), and WHEN HARRY MET SALLY (1989) added to the archive. Getting a full-blown, uncensored f-bomb into the MCU is the big news on the cinematic f-bombs front, but the real highlight is Meg Ryan letting Billy Crystal have it. cinematicfbombs.com

New Releases This Week:

(Review links where applicable)

Opening Buffalo-area theaters 8/11/23 -

BHOLA SHANKAR at Regal Elmwood, Transit & Galleria

CATVIDEOFEST 2023 at North Park Theatre

GADAR 2 at Regal Elmwood

GRAN TURISMO: BASED ON A TRUE STORY at AMC Maple Ridge; Regal Galleria & Quaker

JAILER at Regal Elmwood & Transit

JULES at Dipson Amherst; AMC Market Arcade; Regal Elmwood, Transit, Galleria & Quaker

THE LAST VOYAGE OF THE DEMETER at Dipson Flix & Capitol; AMC Maple Ridge & Market Arcade; Regal Elmwood, Transit, Galleria & Quaker

OMG-2 at Regal Transit

Streaming from 8/11/23 -

ALL UP IN THE BIZ – Showtime via Paramount+ on 8/11

THE COMMUNION GIRL – Shudder on 8/11

HEART OF STONE – Netflix on 8/11

RED, WHITE & ROYAL BLUE – Prime on 8/11

SCENT OF TIME – Max on 8/15

MIGUEL WANTS TO FIGHT – Hulu on 8/16

I LOVE YOU, AND IT HURTS – Max on 8/17

Now on VOD/Digital HD -

GEOGRAPHIES OF SOLITUDE (8/8)

“Lucas captures it all as data while Mills unleashes the artistry of those numbers courtesy of sight and sound. Beauty lives in death. Suffering is born from life. Everything is connected.” – Full thoughts at The Film Stage.

THE LAST RIDER (8/8)

SCARLET (8/8)

SPIDER-MAN: ACROSS THE SPIDER-VERSE (8/8)

“You'd be having the time of your life even if the filmmakers decided to phone the plot in. That they didn't results in a dense work that stimulates the senses more than even INTO THE SPIDER-VERSE could.” – Full thoughts at HHYS.

SQUARING THE CIRCLE (8/8)

“This isn't a documentary on album design. Corbijn's assignment was Powell and Thorgerson's partnership. So, rather than gain insight into the industry, the film's worth is in its captivating stories about the phenomenon that was these two men.” – Full thoughts at HHYS.

WHO DONE IT? THE CLUE DOCUMENTARY (8/8)

THE YOUTUBE EFFECT (8/8)

“An expansive look at how damaging technological growth on an unprecedented scale proves when put in the hands of cutthroat opportunists left to police themselves so a largely apathetic government can willingly reap the benefits of letting them.” – Full thoughts at HHYS.

TRADER (8/10)

3 DAYS IN MALAY (8/11)

COBWEB (8/11)