It’s always wild to me when a festival announces its winners so early in its run even when I know it shouldn’t. When you’re dealing with juried competitions, you don’t need to wait for audiences to see them. It actually makes more sense to hand them out first so that the audiences will see them. No better advertisement than a trophy.

The Cheval Noir Award for Best Feature went to LES CHAMBRES ROUGES. Best director to Sam H. Freeman & Ng Choon Ping for FEMME and best screenplay to Pascal Plante for CHAMBRES. Those two won all but a couple main awards with FEMME also taking best male performance and CHAMBRES taking score and best female performance.

The other two titles taking hardware were WHERE THE DEVIL ROAMS with best cinematography (reviewed last week) and VINCENT MUST DIE earning a “special mention” (reviewed below).

Now that August’s Posterized is up at The Film Stage (or will be shortly after this publishes), I’ll hopefully be able to get a handful more Fantasia titles down for my week three round-up on 8/11. Fingers crossed I hear back with a screener for RIVER because I absolutely loved the filmmakers’ previous time travel film BEYOND THE INFINITE TWO MINUTES.

What I Watched:

BROTHER

(now in limited release and on VOD)

There’s so much love jumping off the screen throughout Clement Virgo’s BROTHER. No matter how tragic things might turn, this adaptation of David Chariandy’s novel never loses that sense of attachment whether to a place, a history, a partner, or family. Everything Ruth (Marsha Stephanie Blake) does is for her boys. Everything they do is for her. Sometimes it’s unnecessary and sometimes it’s counterproductive and harmful instead, but the weight and responsibility these characters hold is always immense and pure and true.

The question then is how do they traverse the minefield that is loving in a world full of hate? You stick close. You dream. That’s what Ruth did bringing young Francis (Jacob Williams) and Michael (Sebastian Nigel Singh) to Canada. That’s what Francis (Aaron Pierre) does when he decides to quit school and pursue music. And what Michael (Lamar Johnson) does when he takes a leap of faith to pursue starting a life with the woman he’s loved since childhood (Kiana Madeira’s Aisha). You dream and push forward no matter the failures or heartbreak. You hope the pain doesn’t consume you with fear.

Because dread is always present. It’s born from the news, lived experience, and assumptions ignited by silence. It becomes something to fear itself too like when Francis blames Michael despite it really being him who is afraid—refusing to show weakness. There’s a mix of toxic masculinity and assimilation in play. As well as the idea Francis must be strong not only for himself, but also his mother and brother with his father out of the picture. He wears a mask to ease Ruth’s already immense burden and let Michael be more. He listens to old records in his room but steps out as an enforcer in the streets to command respect. He tries teaching Michael that confidence is everything. Until even that stops being enough.

We move between three distinct periods of time in the life of this family: their optimistic yet scary days as boys, the complex push and pull of desire and frustration that marked their late teens, and the solemn present ten years after everything irrevocably changed. Virgo shuffles through each, hinging his segues on emotional resonance as much as narrative parallels—moving from joyful smiles to indignation and eventually defeat.

It’s Aisha’s return to the neighborhood that sparks everything. But her presence forces Michael to look back and want to hide rather than remember. He projects that desire upon his mother too, shielding her from reliving the suffering they both barely escaped from the first time until we can’t help wondering if his need to protect her has actually made things worse. What is it he’s so afraid of anyway? What happened to turn this once bright home into a tomb?

The answers won’t be what you think. At least not completely. What makes BROTHER so riveting is that it plays with expectations in ways that allow us to be surprised. We’re supposed to assume this will be another tragic tale of underprivileged kids caught in a system of violence until we realize Francis has been exploiting that system and preconceptions to escape it on his terms. The script then layers in new revelations to better paint the complicated picture of this hulking yet sensitive man who’d run through walls for those he loved. None of it is introduced to steal focus, though. Only to enhance.

This isn’t therefore a “message movie” wielding hot-button topics like immigration, homophobia, and racism as weapons trained on the audience at the expense of the characters themselves. No, those aspects are merely part and parcel to living as Black men in a world that continues to treat them like second class citizens. Virgo and Chariandy ultimately use them to add to the depth of humanity on display. The contradictions inherent to existence. The point of no return wherein playing the game no longer supplies enough reward to keep pretending.

It’s an intense film as a result. One that winds tighter as it progresses so that its final reveal packs the punch it deserves. By coming in waves of memories and flashbacks, however, that gut punch is also countered by a glimmer of hope very quickly. Virgo is weaving through ups and downs with a deft rhythm to ensure we never get too high or low. And Johnson and Pierre provide the journey the authenticity necessary for its sprawling drama to feel lived. Blake is the heart (cue her grassroots Oscar campaign now), but these men supply its soul.

- 9/10

A COMPASSIONATE SPY

(now in limited release and on VOD)

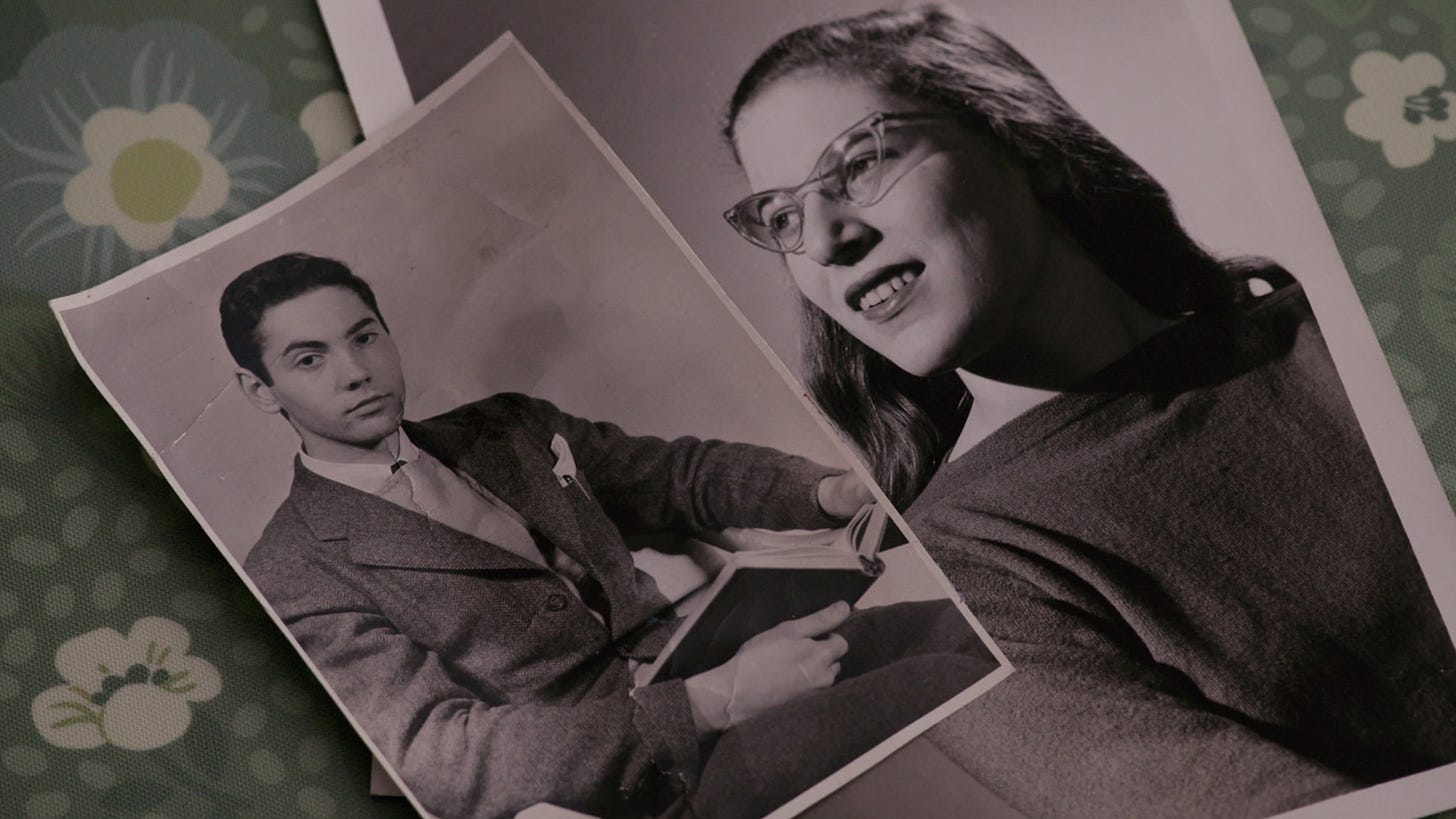

You can’t know the weight of Ted Hall’s decision, as a nineteen-year-old “wunderkind” working on the Manhattan Project, to give the Soviets secrets that would allow them to keep up with America in the nuclear arms race without finding yourself in a similar situation. Other people were there by his side, hooting and hollering when the test bomb succeeded in the New Mexican desert—a reaction that ultimately helped push him to do what he did. Should he have been executed for it like Julius and Ethel Rosenberg? Should they have been executed? Such moral quandaries will never cease to haunt our species.

What really stands out about Hall throughout Steve James’ documentary A COMPASSIONATE SPY is that, while his participation in building the bomb that wiped out hundreds of thousands of Japanese citizens did haunt him, he never regretted his choice to mitigate the potential of America becoming the next Nazi Germany with bankers and industrialists taking over the government for capitalistic motives. With first-hand accounts courtesy of interviews conducted shortly before his death in 1999 proving so, he’d do it all again.

There is necessary context to that reality, though. Hindsight did give him pause once he discovered just how brutal Joseph Stalin was, but he didn’t know that when he passed along his nuclear secrets. So, it goes back to my initial declaration that you cannot know what you cannot know. He cannot know if he would have changed his mind with that information unless he had that information. Maybe the prospect of giving a monster like Stalin this power would have still paled in comparison to his desperate need to ensure the world didn’t succumb to the power it would have birthed by allowing one nation to hold everyone’s fate in its hands.

While the film touches on these internal philosophical debates, it isn’t exactly about what Ted Hall did as much as who Ted Hall was. Don’t therefore come into the experience of watching it with the expectation that it’s solely about the process, deliberation, and aftermath of his being a Russian spy. This is instead more a biopic of the man himself and the life born out of his treasonous act of defiance. And more than that, it’s a love letter to him as told by his widow Joan—the woman he married shortly after his return from Los Alamos and who kept his secret from the moment he admitted it directly after proposing.

As such, this is hardly an objective piece. Including Joseph Albright and Marcia Kunstel, authors of the book BOMBSHELL: THE SECRET STORY OF AMERICA’S UNKNOWN ATOMIC SPY CONSPIRACY, surely helps in that regard, but they’re here to provide anecdotal information and corroboration. It’s Joan who leads the narrative and, while all evidence seems to agree, you cannot ignore she does so through a filter of love wherein he could do no wrong.

You cannot blame James from taking this angle considering the subject matter, though. Just as Hall made his decision with compassion for mankind’s preservation held above blind loyalty to his country, this version of his story centers compassion for Ted above the scorched earth vitriol of a military establishment indoctrinated to see everything as black or white. And if you must choose between the conjecture of someone who spent her life by his side or that of an institution hellbent on insulating itself (James does well to show just how quickly the media and government pivoted from Russia being an ally to anti-“Red” propaganda), the former is the way to go.

This is especially true because Joan is a passionate and entertaining storyteller. She has a wonderful sense of humor and an immovable sense of political and moral responsibility. The film unsurprisingly works best when she’s given the reins (or when archival snippets of Ted speaking for himself are shown), but the many dramatic reenactments filling the gaps aren’t without their charm even if they often render the whole a bit too sanitized and plastic for the trouble.

- 7/10

PASSAGES

(now in limited release)

When Tomas (Franz Rogowski) returns home to his husband Martin (Ben Whishaw) after spending the night away with a woman he just met (Adèle Exarchopoulos’ Agathe), you can feel the embarrassment and awkwardness of the scenario. The assumption is then that he will lie. Deflect. That Tomas will do whatever he can to make certain Martin doesn’t think the worst. So, you can’t help but perk up in your seat when he instead blurts out, “I had sex with a woman. Can I tell you about it?”

It’s the wildest response and yet delivered with such purely innocent excitement. Tomas truly wants to share this experience with the man he loves. Not because they’ve agreed to an open relationship, but because he needs an outlet to work through his feelings and Martin has always fulfilled that role. Tomas doesn’t consider the fact that doing so will hurt his husband, though. In his mind he’s allowed to be selfish because Martin should understand. He always has. Except, of course, Martin hasn’t always been the victim of that selfishness.

Director Ira Sachs and co-writer Mauricio Zacharias have crafted their latest collaboration PASSAGES in a way that throws us directly into the volatile fire of love’s passion and scorn without knowing exactly what to expect. Because it doesn’t appear like this development is a surprise as much as a blow for Martin. He’s obviously angry, but he tells Tomas they’ll talk later. That this is how he acts every time he finishes directing a film. Tomas is an artist. Impulsive. Narcissistic. Things will return to normal.

Unless this has become “normal”? What happens if constant forgiveness and acceptance has pushed Tomas to revolt? Not because he doesn’t love Martin anymore. Or because he doesn’t need him. But because he wants more. He wants the fireworks that arise from making Martin mad. He craves the excitement and uncertainty of blowing up everything safe and comfortable, training himself to think it’s a game rather than a time bomb—for both of them. Because this time Tomas is falling in love. This time Agathe is more than a pawn and Martin is the third wheel forced to face the reality he’s relinquished all control.

It’s a fascinating and complex character study wherein desire gets the best of all involved. Tomas wants his new toy. Agathe wants love. Martin wants escape. But then come the restraints. Tomas finding himself in an even more rigid example of domesticity. Agathe realizing she’s playing second fiddle to his career and former life. Martin wondering if the new artist he’s found (Erwan Kepoa Falé’s Amad) is real or just his own self-destructive nature filling the void of love with a familiar facsimile. Now Tomas wants Martin back. Agathe wants freedom. They all want to be heard.

What’s interesting, though, is that Sachs doesn’t focus on the two characters who’ve earned our sympathy (Martin and Agathe are rarely given any screen time dictated by their own perception). His lead is instead the one who causes them so much pain. Because while they all want to be heard, only Martin and Agathe are also willing to listen. Only they are ready to sacrifice that which they want to ensure Tomas is being heard too.

He refuses to do the same. He might be incapable of it. When a conversation goes awry, Tomas just leaves. When someone tells him to go, he’ll fight to stay. This isn’t therefore a story about a troubled man seeking answers. It’s about a troubled man demanding answers and, in turn, opening the eyes of those who love him to the truth that he’ll never love anyone but himself.

The film’s complex and intelligent script mines the emotions that go into the intermingling of love, lust, and desire. There’s the unconditional love Martin and Agathe give Tomas and the ways in which he exploits it for personal gain. Whishaw and Exarchopoulos are great as always giving life to their tragic journeys, but Rogowski is unforgettable as the man causing them such unspeakable pain. Because nothing Tomas does is malicious. I’m not even certain you can call it intentional. But it hurts. It destroys.

PASSAGES works so well and feels so refreshing because it flips the usual redemption formula. Instead of teaching Tomas the error of his insidiously domineering way, it opens the eyes of his victims (and ours). It highlights how humans ignore red flags and compromise themselves for something that isn’t real while also understanding their oppressor’s genuine sorrow is irrelevant once they’ve found the strength to let him go. That sorrow doesn’t earn empathy as much as pity for his confusion. Hopefully we’d do better to recognize our own fault in a similar situation.

As for the NC-17 rating: Wow. If this isn’t an egregious example of the MPAA classifying gay sex as “explicit” simply for being gay, I don’t know what is. Zero nudity beyond one flaccid penis in a non-sex scene. That’s it.

- 8/10

Fantasia International Film Festival

A DISTURBANCE IN THE FORCE

(international premiere)

“Coon and Kozak show that The Star Wars Holiday Special truly exists on an island alone as an unwitting cautionary tale never to be repeated again.”

– Full thoughts at The Film Stage.

EMPTINESS

(world premiere)

If you’re going to hinge your film on a “surprise” reveal that renders the whole moot either by an unreliable narrative or “dream” conceit, you need to make sure that the fiction you’re presenting to the audience is also compelling enough on its own to sustain their attention. That’s sadly not the case with Onur Karaman’s EMPTINESS. Maybe it’s the fact we know something bigger is happening from the first scene or maybe it’s the circuitous nature of the whole, but I checked-out before I even had the chance to check-in.

The main reason is that the disappearance of Suzanne’s (Stephanie Breton) husband Normand seems to be the central mystery despite never being expounded upon until the eleventh hour. Besides her laments and the response of mounting hostility and calm indifference from her caretakers Nicole (Anana Rydvald) and Linda (Julie Trépanier) respectively, the subject proves little more than a distraction from the fact nothing is happening. It’s just Suzanne sneaking out to the barn to see a “woman in white”. Nicole screaming at her for leaving. And Linda sowing seeds of distrust in Nicole's direction. Rinse, repeat.

Some of the imagery is legitimately captivating and some of the horror elements build a modicum of suspense, but nothing ever comes from it. And, as a result, it's impossible not to take notice of the “hidden” details. The fact Nicole never acknowledges Linda’s presence or that Nicole never lets Suzanne answer the phone. The entire film becomes a waiting game, testing our patience to see if we can endure the monotony long enough to receive an answer. Unfortunately, I’m not sure that answer is worth the effort for those who do.

Because while the truth of what’s happening makes sense, it doesn’t have purpose beyond its “a-ha” moment. There’s no insight or additional drama. All that remains when it arrives are the credits. Karaman has therefore only provided a hollow metaphor, stylistically building an interpretation of what it’s like to be trapped inside one’s head as a result of illness. EMPTINESS is an experiential approximation of the isolation, confusion, and fear (real and perceived) felt by those unfortunate souls who must contend with a debilitating disease. It’s a ride through the unknown. A detached and disposable journey devoid of substance.

- 4/10

VINCENT MUST DIE [Vincent doit mourir]

(North American premiere)

Which is more plausible? That a bunch of random people want to kill you for no discernible reason? Or that a bunch of random people want to kill you because you did something to provoke them?

Our species loves to ascribe purpose to actions because we cannot comprehend a world without it. That’s why we try to project reason onto the unreasonable and pretend systems built to disenfranchise are actually working incorrectly rather than exactly as planned. It’s not therefore that humans are “good” at their core. It’s that we believe the humans surrounding us are to stay sane. That they’re just prone to errors like the rest of us—confused lambs, not malicious wolves.

It’s not therefore surprising when everyone inherently blames Vincent (Karim Leklou) for getting attacked. He must have provoked the intern into hitting him in the face with a laptop. He must have pissed Yves (Emmanuel Vérité) off to earn a series of stabbings with a pen. Because that belief makes more sense than a reality where violence erupts without cause. It makes more sense to fear Vincent (what he’s apparently stirring up or his inevitable retribution) than worry that we might also be targeted. Logic must prevail despite our world’s illogical descent.

Director Stéphan Castang and screenwriter Mathieu Naert’s VINCENT MUST DIE is thus as much a political statement about today’s rising current of rage-fueled responses to society’s so-called ills as it is a new spin on the zombie flick as already reinvented by Joe Lynch’s MAYHEM. Unlike that film’s virus pushing everyone to want to kill everyone else, however, the urge to destroy here possesses a more specific target. And rather than originate from the aggressor, this bloodlust is sparked by the victim. It’s as if Vincent is secreting a pheromone that makes anyone who locks eyes with him want to bash his skull.

The result is as humorous as it is horrific. We can’t expect when the next attack is coming or how brutal it might be, but we can laugh when the absurdity of the situation leaves everyone unable to fully process what occurred. Vincent’s bosses and HR department look to mediate. Vincent quickly forgives so as not to rock the boat. Yves breaks down in tears knowing what he did without having any recollection of doing it. And things only get wilder when children attack him. Or when Vincent meets someone else suffering the same plight (Michaël Perez’s Joachim). Or when he falls in love (with Vimala Pons’ Margaux).

That’s where the fun and intrigue lie since this isn’t some high concept gore-fest of carnage like MAYHEM or THE SADNESS. Castang has crafted a quiet drama out of the scenario instead—one where its victim just wants to stay alive and, hopefully, not be forced to kill someone else knowing they can’t help themselves. Steering clear of mankind isn’t easy in this day and age, though. Neighbors knock on the door. Delivery people ring the bell. Restaurants need to serve you their food. And the more you avoid eye contact, the more hostile and suspicious they become.

I didn’t expect VINCENT MUST DIE to carry through as far as it does. I thought this would just be a bit of a lark wherein the lead character must endure his curse until an answer or cure arrives. So, it proves quite surprising and appreciated when the world is expanded via both the events Vincent experiences and the gradual escalation of news stories on the radio. What starts as an isolated phenomenon soon grows until its impact can no longer be ignored.

That romance finds a way to blossom anyway can feel corny, but it’s also necessary. Its incongruous nature to the subject matter adds comedy while its ability to make a man forget his entire species wants to murder him still proves sweet. Because what epitomizes love more than the desire to make it work in a world that’s seemingly erased it from its vocabulary? Have you ever loved someone so much you’d risk them choking you to death in your sleep to be together?

(Context is everything since that’s a question with obvious domestic abuse undertones—enough to probably earn the film a trigger warning with how quickly its concept demands its victims blindly forgive their abusers.)

- 7/10

WITH LOVE AND A MAJOR ORGAN

(Canadian premiere)

It’s difficult to watch when some people seemingly go through life without caring about the consequences of their actions. We wonder what it must feel like. We wonder if it’s a product of selfishness or heartlessness and whether there’s even a difference. And we imagine that those on the other side don’t wonder at all since they can’t know what it is they’re missing. They label us suckers. Rubes. They embrace that lack of feeling as strength. Enviably, some of us do too.

Because we can get so caught up in the wake of grief, sorrow, and regret that we yearn to close ourselves off in much the same way. Push it away. Pretend it means nothing. But doing so inevitably forgets the fact that losing those painful emotions also means losing the ones that spark joy. It’s that old saying about love and loss and the need for both to ensure either can be truly meaningful. The alternative isn’t therefore better at all—especially not when you still remember what it was to feel the good things. Oftentimes it actually proves worse.

Director Kim Albright and screenwriter Julia Lederer’s smart and witty surrealist dramedy WITH LOVE AND A MAJOR ORGAN seeks to give shape to this reality for both the characters on-screen and us. It also looks to illustrate a new middle ground that’s swept through society via social media algorithms, emboldening people to mitigate their suffering by avoiding all emotions through the dissolution of choice. Because letting a phone app dictate your likes and desires isn’t about streamlining those things. It’s about facilitating the systematic destruction of individuality. That’s what ultimately causes so much pain. Anything that makes you special enough to love is also ripe for conjuring hate.

Anabel (Anna Maguire) craves that duality. She looks at her best friend Casey’s (Donna Benedicto) sanitized life of phone dings and finds herself rejecting the prospect of such homogenization even more. She wants to find love, but on her terms. And she’s willing to suffer heartbreak if it doesn’t work out. Because it won’t. Not always. There’s as much a chance of being turned down by the analog soul reading his newspaper on the next park bench (Hamza Haq’s George) as there is reciprocation.

That uncertainty is what Casey thinks she has excised from her own life when what she’s really removed is the space for personal taste in order to never feel out-of-place. She still feels emotions. She still knows what it feels like to be othered and to be the one doing the othering. It’s why she won’t just tell Anabel “No” when the latter makes suggestions about her impending nuptials. Casey doesn’t want to hurt her maid of honor, but she also doesn’t want to alienate the carefully curated guests her app has decided are crucial for her prolonged happiness.

So, Anabel is heading for a fall on multiple levels. Romance. Friendship. Even her mother avoids hard conversations to make her think things are okay when they most certainly are not. It leads to a turning point where Anabel has had enough. If no one wants her to love them the only way she knows how (messily, loyally, completely) and she doesn’t want to carry the hurt piled upon her by that refusal, she’ll simply rip her heart out of her chest. Maybe then she can just exist like everyone else.

It’s a gruesome yet beautiful concept that Albright and Lederer manifest through unforgettable visual metaphor. Add Anabel’s decision to give the heart to George—a man whose only response to her vulnerability is to say “I can’t”—and his mother’s (Veena Sood’s Mona) complicated relationship with contented conformity and violent aggression and the second half of WITH LOVE AND A MAJOR ORGAN perfectly weaves through the complex, unforeseen effect our love has on those around us. Casey getting frustrated at Anabel for being so extra doesn’t mean she won’t miss it when it’s gone.

What ensues is a humorously poignant journey towards understanding that our love can inflict pain onto others just as easily as it can onto ourselves. Mona’s love has prevented George from truly living. Anabel’s love has made her immune to seeing what’s really going on. George’s lack thereof makes him a junkie to it the moment he first feels its indescribable awe. Our tears will therefore always be worth the torment because we’d be nothing without them. They are love’s truest form. They remind us that we’re still alive.

- 8/10

Cinematic F-Bombs:

This week saw ARMED AND DANGEROUS (1986), CRAZY/BEAUTIFUL (2001), THE IN-LAWS (2003), THE MARINE (2006), and WHO’S HARRY CRUMB? (1989) added to the archive. He may not be the one dropping the f-bomb, but it’s fun to add a couple new John Candy films to the collection. cinematicfbombs.com

New Releases This Week:

(Review links where applicable)

Opening Buffalo-area theaters 8/4/23 -

DREAMIN’ WILD at AMC Market Arcade; Regal Quaker

THE MEG 2: THE TRENCH at Dipson McKinley, Flix & Capitol; AMC Maple Ridge & Market Arcade; Regal Elmwood, Transit, Galleria & Quaker

TEENAGE MUTANT NINJA TURTLES: MUTANT MAYHEM (opened 8/2) at Dipson McKinley, Flix & Capitol; AMC Maple Ridge & Market Arcade; Regal Elmwood, Transit, Galleria & Quaker

Streaming from 8/4/23 -

DIVINA SEÑAL – Prime (8/4)

THE SEVEN DEADLY SINS: GRUDGE OF EDINBURGH, PART 2 – Netflix (8/8)

UNTOLD: JOHNNY FOOTBALL – Netflix (8/8)

COOKIE MONSTER’S BAKE SALE – Max (8/10)

LOVE IN TAIPEI – Paramount+ (8/10)

MARRY MY DEAD BODY – Netflix (8/10)

Now on VOD/Digital HD -

INSIDIOUS: THE RED DOOR (8/1)

THE NIGHT OF THE 12TH (8/1)

“This police procedural isn't therefore about justice or heroism or even violence. At least not any one isolated from the others. It's a look at the human condition and its tragic flirtation with futility.” – Full thoughts at HHYS.

RIVER WILD (8/1)

YOU HURT MY FEELINGS (8/1)

“Keeping a little mess involved isn't always a bad thing and I do believe YOU HURT MY FEELINGS could have benefited from more. The film can therefore feel a bit too perfect in its cause and effect, but the comedy sells itself.” – Full thoughts at HHYS.

BLACK ICE (8/4)

“Davis does well to never let the good or bad overpower the complexity of the full picture so his audience realizes things are simultaneously moving in the right direction while still being a long ways away from "fixed."” – Full thoughts at HHYS.

BROTHER (8/4)

Full thoughts are above.

A COMPASSIONATE SPY (8/4)

Full thoughts are above.

LOLA (8/4)

THE PASSENGER (8/4)

WHAT COMES AROUND (8/4)

“It's a devastating series of revelations met with heartrending gravitas to make us question our loyalties and prejudices. Roost is a story without winners because none of them are innocent. Not fully anyway.” – Full thoughts at The Film Stage.